Walter Block and the Prisoner's Dilemma (UNLOCKED)

Reflections on my most recent debate with Walter Block and, more generally, libertarians' use of the "socialism is fine if it's voluntary" deflection.

I just debated libertarian economics professor Walter Block. It’s the third debate I’ve done with him over the years. The first one was in 2020, which now feels about as recent as the Ford administration. The second, which happened last year after an exchange of articles in Merion West, was on Gaza. (I also wrote about that debate here.) Our fundamental disagreements on economics had flared back up around the edges of that second debate, and afterward Walter proposed that we do it all again (the exchange of articles followed by the YouTube debate) but on capitalism and socialism.

You might wonder why I said yes. Walter is, after all, a deeply odd person with some truly vile views, and by the time he made the suggestion I’d already given him quite a bit of my time. Why go back to that well again?

Part of the answer, I’m sure, is just that I find him fascinating almost as a literary character. He went to high school with Bernie Sanders. (They were on the track team together.) He’s extremely excitable. He has a habit of illustrating his arguments with examples about whatever objects happen to be lying around on his desk. He’s downright passionate about exactly how many minutes and seconds each participant in a conversation is given to make their points.

And then there’s the content. In this most recent debate, for example, he argued at one point that we should privatize the roads precisely because different private road-owners would be able to set speed limits wherever they liked. In his mind, it’s just obvious all this experimentation in what speeds it was safe to drive at would work out in the long run make roads safer. Some of my fascination might be as simple as having no idea what he might say next.

Beyond all that, though, I actually find it interesting and even intellectually useful to engage with him because I find almost all of his views to be so deeply alien. It helps that, unlike the YouTube personality Steven Bonnell (aka “Destiny”), for example, who I’ve also debated three times over the course of the last several years, Walter really does see debates as battles between ideas more than battles of egos. While Bonnell tends to wander away from the original topic to go fishing for any tangentially related subject on which he thinks he can make his interlocutor look bad, Prof. Block actually cares about the issues in dispute. He wants, very badly, to show that he’s right. And he’s not a stupid man. He has moral values I find bizarre, and he often assumes factual premises that feel like dispatches from an alternate reality, but the effect of it all is to make you work to show that he’s wrong about it all. You learn things along the way.

The written exchange leading up to this debate started with an essay from me called The Case for Democratic Socialism. In his response, Walter took issue with use of the phrase “the domination of society by wealthy interests.”

He wrote:

Under pure laissez-faire capitalism, the system I defend against socialism, there is no force or fraud. Those are crimes. How is it supposed that the “wealthy interests” gain their station in the first place? There is one possibility—and only one possibility: They make an offer that the recipient of the offer “cannot refuse.” Why cannot he refuse? This has nothing to do with The Godfather. He cannot refuse because it is not in his best interest to refuse. For example, suppose we start off under a system of perfect financial equality. All people in the society have the same amount of money. They are all independent entrepreneurs, each one working solely for himself. Each is as productive as every other person. However, A saves part of his funds and B does not. A then offers B an employment contract. “Come work for me,” says the former to the latter, “and I will pay you $X.” $X is more than B can earn for himself on his own, so he agrees.

How can A afford to pay B this amount of money? Where is this extra productivity coming from? It emanates from economies of scale. The two of them, A and B, working together—B under the direction of A in this case— can produce more than double the amount of goods and services than each one can do so on his own. The point here is that there is no exploitation of any kind going on here. Each and every commercial interaction in the marketplace is one of mutual benefit. A pays B $X, but he earns $Y from this deal, where the latter is greater than the former. A sells the product that he and B have produced to C at the price of $Z. C agrees to the purchase. Why? That is because C values the product at a higher level and, thus, earns a profit on the deal. Without any exception, all commercial activity is mutually beneficial, at least in the ex-ante sense, and usual ex post as well (I buy a pair of shoes for $50. At that time, ex ante, I necessarily valued it at more than that amount; otherwise I would not have made the purchase. Later on, ex post, I may come to regret this decision.).

In my reply, I granted that there’s a “narrow sense” in which his premise is true:

In the particular circumstances in which someone finds himself at a particular moment, no one would buy or sell a product (including selling their working hours to a capitalist) if it were not more advantageous to them to do so than whatever alternative options were available to them in the moment.1 Of course, how those circumstances arose and how (and why) the options available in the moment were restricted is often a different matter. (Think, for example, of the initial rise of modern industrial capitalism in Great Britain, which was facilitated by the enclosures which mass expelled the British peasantry from their ancestral land and made them desperate enough that accepting factory work suddenly became “mutually advantageous” to them and their new bosses.)

But even if capitalism had been as immaculately conceived in real history as in the most pleasant daydreams of philosophers such as Robert Nozick or Murray Rothbard, the inference from the micro-level individual transactions (A agrees to work in B’s factory, C buys B’s products) being mutually advantageous to all participants in the moment to the conclusion that the macro-level social arrangements that emerge from all this must be in the interests of the majority of the population blatantly commits the Composition Fallacy. It is like moving from the premise that all the individual molecules in the Brooklyn Bridge are invisible to the naked eye to the conclusion that the bridge itself is invisible. A secretary who takes a job where she has to put up with the groping of her boss to keep her position is making a decision more to her advantage than being thrown into unemployment (especially if she lives in an anarcho-capitalist society [like the one Walter advocates] with no unemployment benefits). Nevertheless, laws against private-sector sexual harassment are in the interests of secretaries.

In the YouTube debate, I made a quicker version of the same point about sexual harassment laws. Sticking with the position he took in his old article on the topic (which inspired my use of the example), Walter bit the bullet, saying that he didn’t see why I’d want to throw a “pity party” for a secretary who decided that it was more advantageous to become, in effect, a “part-time secretary and part-time prostitute” than to become unemployed. Prostitutes, he reminded me, sometimes make “good money.”

As I said, the man has a deeply alien value system. But, on some level, I also find his willingness to embrace this frankly insane conclusion refreshing, if only because he’s so much more consistent than most people who make libertarian arguments against socialism that exactly mirror the logic of his defense of groping bosses.

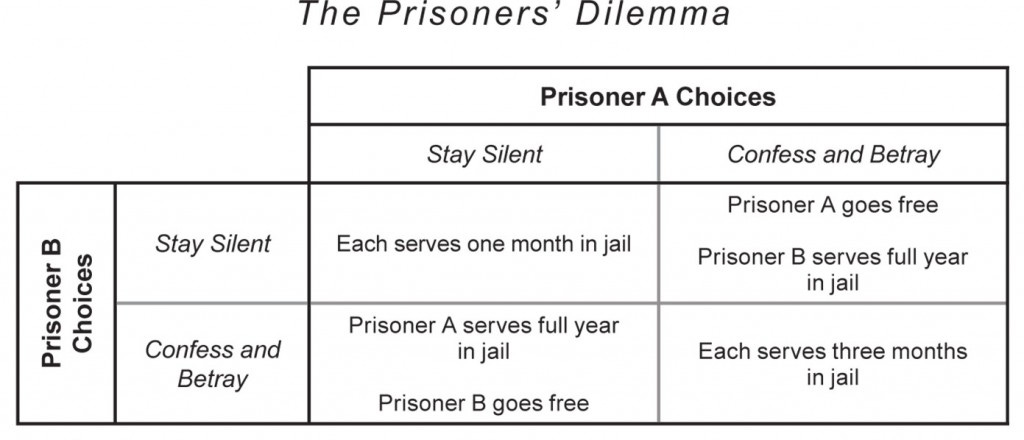

A different way of making pretty much the same point I made by talking the molecules in the Brooklyn Bridge might have been to get into the Prisoners’ Dilemma. Two people have been arrested for some minor crime (the standard sentence is just a year of imprisonment) in a country whose laws require the authorities to release them after a month if there isn’t enough evidence for a conviction. In this case, the only way to make the charges stick would be for one of them to confess and betray the other. So, the authorities individually offer each one a deal. If one confesses and the other doesn’t, the one who confesses will be released immediately while the other will spend the full year behind bars. If both confess, both sentences will be reduced to three months.

Even putting aside any questions of honor or loyalty to exclusively focus on rational self-interest, it would pretty clearly be a good idea for the prisoners to coordinate and both keep their mouths shut so that they could both get out after a month. If coordination is impossible, though, the thing that’s in each prisoner’s interests is to betray the other.

Would Walter Block deny that the thing that’s in Prisoner A’s interests (in the no-way-to-coordinate scenario) is to rat out B, and vice versa? If not (and if we can agree that it’s worse for both A and B to spend three months in prison rather than just one month), it’s hard for me to see how he could avoid conceding that it’s entirely possible for individual-level decisions that serve the interests of everyone involved more than other alternatives available to them in the circumstances they individually find themselves in to nonetheless work out to the severe disadvantage of most of the people involved.

In the debate, I made a standard argument for social democratic reforms like Medicare for All (that people have a right to have their basic needs met) and an equally straightforward argument for going beyond social democracy to outright socialism (that democracy is good and valuable and shouldn’t stop at the entrance to the workplace). In response, Walter chowed down on a good number of bullets. (Why shouldn’t we have “two-tier healthcare” for the rich and the poor, he asked?) He also made a standard libertarian argument that will sound reasonable to many ears. A healthcare plan that covers everyone is fine, but why should people be forced to contribute to it? And workplace democracy is all well and good if people voluntarily start worker co-ops. “No one is stopping you.”2 In general, “Ben will be happy to know,” Walter has no problem with “voluntary socialism.” It’s the force that bothers him.

There are three problems with all this. First, at the most obvious level, the value being appealed to by Walter’s voluntariness talk (individual autonomy/non-coercion) may be an important one, but there are other relevant values to balance it against. Human needs matter. Equality matters. Two-tiered healthcare, for example, really is a moral obscenity. Even if we believe in individual autonomy enough to, for example, be pretty uncompromising about pregnant women’s right to control their own bodies, George Kateb’s response to Nozick’s libertarian treatise Anarchy, State and Utopia feels pretty relevant here. "I find it impossible to conceive of us as having nerve endings in every dollar of our estate.”

Many leftists would regard this as a sufficient response to economic “voluntariness” arguments and I basically agree, but I think it’s a mistake to leave things here, both because there are interesting things to notice if we keep going and because leaving it here concedes far too much to the libertarian opposition.

The second problem with Block’s argument is the one I learned from Matt Bruenig and G.A. Cohen. When libertarians say that it’s unacceptably coercive to take away your property, what do they mean by “your”? They can’t mean the property that currently happens to be in your possession, or else recovering stolen property would be unacceptable. They can’t mean the property you’re legally entitled to, or else nationalizations carried out through proper legal processes would be fine. They have to mean property you’re morally entitled to. And “it’s wrong to take away property that the person you’re taking it from is morally entitled to keep” is just a convoluted way of saying “it’s wrong to take property that it’s wrong to take.” It’s totally uninformative. All the work is always being done by the substantive moral theory of who’s entitled to which resources.

Should we an adopt an egalitarian theory of just distribution, or a Lockean one where even wildly unequal distributions are fine if they come about the right way? (And, if we opt for a Lockean approach, how does it map onto the economic history of the real world, where distibutions of property generally haven’t come about the right way?) The real debate is always about questions like these, and trying to change the subject to “freedom” or “non-aggression” by talking about the wrongness of taking what people are entitled to keep is either circular or a distraction. As I said in the debate, it’s the philosophical equivalent of the street magician’s tactic of talking the whole time he does his trick so you look at his face instead of his hands.

But there’s a third problem with Walter’s oh-so-generous acceptance of hypothetically “volunary” socialism. And, to see what it is, it’s helpful to think about comparisons to sexual harassment laws, workplace safety laws, minimum wage laws, and so on. In all of these cases, you could say, “hey, I’m fine with ending workplace sexual harassment, guaranteeing safe working conditions, establishing a floor for wages, and so on, as long as long as it all happens voluntarily.”

By analogy to the “Why don’t you go off and start a worker co-op and outcompete all the capitalists if you want to bring about workplace democracy?” challenge, you could ask (at a point of history before such laws were put in place), “Instead of using the coercive power of the state to stop workplace sexual harassment, why don’t you just start some companies with strict anti-harassment policies and outcompete the firms where harassment is rampant?” Or, companies with strict safety standards. Or, companies with a high wage floor. After all, no one is stopping you!

As the second and especially third of these examples suggest, one initial problem with this line of thought is that companies where these sorts of pro-worker internal policies have been implemented will be at a competitive disadvantage to companies without such policies. If you can get away with paying poverty wages and exposing workers to unsafe conditions, you can squeeze more profits out of them. And this point applies in spades to workplace democracy. All else being equal, firms where labor and capital are separated have some pretty obvious competitive advantages, ranging from their ability to raise initial capital by giving investors ongoing ownership shares to the obvious fact that it’s a lot easier to move from place to place in pursuit of better business conditions when the workforce doesn’t have to move with the company. This is entirely consistent with the possibility that, if all private firms were worker-owned, we could still have an economy that worked well to meet everyone’s needs. Certainly, in the real world, we’ve proven that minimum wage and workplace safety laws are fully compatible with a thriving economy, even though individual companies are at an obvious market disadvantage if they adopt such policies unilaterally.

Next, notice that even sexual harassment has never been effectively combatted through the “just outcompete the harassers” strategy, even though there’s no obvious reason why firms would become less profitable when they adopt anti-harassment policies. This suggests that the competitive disadvantages faced by firms that pay people more or cut fewer corners on safety (never mind firms that have been taken over by the workers themselves), while very real, aren’t the only or perhaps even the main reason none of these forms of progress have ever come about through the “just work through the market” strategy (as opposed to coming about as a result of the regulatory state, a militant labor movement that doesn’t respect capitalist property rights, or some combination of the two).

Another libertarian economist I’ve debated, Gene Epstein, likes to point out that the whole working class, in the aggregate, exercises tremendous buying power as a mass of consumers. As such, it could collectively act to make worker-ownership the economic standard, within the rules of the free market, simply by boycotting targeted firms until they agree to sell to their own workforce. As with Walter Block’s “voluntary socialism”/”no one’s stopping you” talking points, Epstein’s insinuation is that, if this doesn’t happen, that reveals a widespread preference for maintaining the economic status quo.

Again, though, why didn’t the power of boycotts bring about a wage floor with no need for minimum wage laws? My debate with Gene was in The Villages in Florida. As I pointed out in that one, just a few months earlier Florida voters had passed a ballot measure to institute a $15 minimum wage. That was so popular that, running the numbers, it looks like plenty of Floridians voted for both a $15 minimum wage and Donald Trump. Why didn’t those same voters achieve the same result simply by boycotting every firm whose lowest-paid employees got less than $15 as they wandered the aisles at Publix or Winn-Dixie tossing items into their carts? Why have decent workplace safety standards never come about that way? Why hasn’t the need for sexual harassment laws ever been obviated that way? Women, after all, not only make up half of the population but, especially at the time when American society was far more sexist than it is now and workplace sexual harassment was far more rampant, they did the vast majority of the grocery shopping.

In my most recent debate with Walter Block, he said that we get to “vote with our dollars” far more often than we vote with our votes. That’s true enough. But even apart from the extreme undemocraticness of “elections” where “votes” are so unevenly distributed through the population, there are two problems here, both of which point to ways in which actual democratic politics can help solve the collective action problems presented by the million little Prisoners’ Dilemmas built into day-to-day market interactions.

First, when a Floridian spends the 5-10 seconds she’ll likely take to decide which breakfast cereal to throw into a cart at at Winn-Dixie, she’s not just “voting” on whether she approves of the wage floor at each of the rival cereal producers. In fact, quite likely she’s not voting on that at all, since she won’t have this information. But even if a couple of activists were standing outside the sliding doors at the front of the store handing out fliers with handy lists of common products made by companies that pay less than $15 an hour (and a lit of alternatives made by higher-paying competitors), so her decision is in part a “vote” about the wage floor, it’s also a vote about a lot of other more immediately pressing issues, like how much money she’s willing to spend on a box of breakfast cereal and whether her kids prefer the taste of the other brand. By contrast, if that same consumer/voter has a chance to vote for a social democratic politician who campaigns on raising the minimum wage and a raft of related egalitarian measures, the aspect of her vote that’s specifically about the minimum wage is far more disentangled from unrelated issues. And if she has a chance to vote for a ballot measure to raise the minimum wage, the issues have been as disentangled as they possibly could be.

Second, the risk/reward tradeoff is far better in the case of literal voting. If you pay higher prices for non-boycotted products for a protracted period of time while you’re giving a boycott a chance to work, and not enough others join you for, you’ve materially lost out while gaining nothing in return. By contrast, whether or not enough of your fellow voters follow your lead, all you lose by voting is a few minutes of your life once every couple of years. Little wonder a majority of Floridians voted to raise the minimum wage while trying to organize the same number of people as consumers and keep them in the fight for long enough for the boycott to work would have been a monumentally more difficult undertaking, and trying to enforce a $15 wage floor that way would have involved that process playing out for each individual company.

Concluding that Floridians didn’t “really” want a higher minimum wage because they were only willing to cast literal votes and not engage in the libertarian economist-approved preference-revealing procedure of voting with their dollars would make as little sense as saying that if (a) two prisoners who do find a way to make a binding agreement both keep their mouths shut, but (b) those same two prisoners would have both confessed if they hadn’t had a way to make such an agreement, this proves that (c) their true underlying preference is to each serve three months in prison. Maybe this is simple-minded of me but it sure seems like, if the majority of the public votes for a higher minimum wage, that’s the best sign you could hope for that most of them want a higher minimum wage. Similar points would apply if a majority of the public democratically voted for a socialist government that nationalized the means of production and put them under workers’ control.

One important caveat.

Even modestly successful social-democratic movements tend to be built on the basis not just of electoral efforts but workplace-level organizing, and this is a kind of organizing that does have to overcome stubborn collective action problems. Individual workers have powerful incentives to keep their heads down and not risk their livelihoods. As I wrote a while back (summarizing arguments that Vivek Chibber makes in his excellent book The Class Matrix), whether

any given iteration of the workers movement will expand and solidify itself or contract and become vulnerable to defeat [depends] in large part on whether it’s been able to put points on the board, wins in collective struggle that will change individual workers’ risk-reward calculations going forward. In the absolute best scenario, there can be virtuous circle in which solidaristic culture-building can help a movement along to a point where it can deliver material wins that change the risk-reward calculations and this helps build solidarity going forward…

As Chibber emphasizes, this is a difficult long-term process and a thousand things can go wrong. There’s a reason we aren’t living under socialism yet. Even modestly successful workers’ movements have been far more the exception than the rule in the history of capitalism.

Without understating the difficulties, though, the fact remains that these collective action problems have been historically far more tractable than those involved in organizing people as consumers (which is to say, organizing them in the sphere of their lives in which they’re the most atomized). The workplace context is vastly more conducive to collective decision-making and collective action.

All of which, I suppose, is just to say that questions like “why don’t you go off and start worker coops through existing market mechanism?” or “why don’t you just use the power of the working class as an enormous block of consumers to bring capitalists to their knees?” have a very boringly simple answer:

”Because there are straightforward predictable reasons why that won’t work, so instead I’m pursuing the strategy that actually might work.”

I understand perfectly why someone might try to insist that his ideological enemies pursue a strategy that can’t work. But the rest of us aren’t obliged to take the advice seriously.

As Nathan Robinson pointed out after this article came out, even this formulation concedes too much. I really should have said “if they didn’t think it was more advantageous to them to do so than whatever alternative options were available to them in the moment.” I don’t want to put too much emphasis on this point, though. Nathan is clearly correct that participants in real markets often lack all sorts of relevant information but I don’t think that’s the main thing that’s wrong with Walter’s argument.

You might be able to say, especially if you’re bullish on the prospects for solving the calculation problems afflicting centralized planning, that the “no one is stopping you from starting a co-op” objection is irrelevant to you, because you don’t want co-ops, you want real socialism. But this response won’t do as much work as you might hope. At best it shows that not all aspects of what you want can be achieved by Block’s “voluntary” mechanism. To whatever extent that your case for real socialism relies on the undemocratic nature of capitalist workplaces, his argument is still relevant. For better responses, keep reading.

Ben, I think that you are still conceding too much to libertarians on the issue of property and nonaggression. The nonaggression principle is a pretty good principle if used sensibly, and it puts supporters of strong private property rights on the defensive. Private property in tangible things is impossible without aggression - my house and my car are not really mine if I can't stop other people from using them, by initiating force if necessary (or calling on the state's monopoly of force). In the case of things like my house and my car, the aggression might be justified on fairness grounds. I worked hard to earn these things, and I will lose the benefit of my sacrifice unless I have exclusive use of them, enforced by the threat of aggression.

But the presumption against aggression is hard to overcome when it comes to large amounts of wealth, especially wealth that was not earned through sacrifice. Supporters of capitalism should have to answer the question: what justifies aggressively excluding people from unearned private property?

Also, two snappy responses on the argument that a system that runs on mutually beneficial transactions must be good.

1. It ignores externalities.

2. If you put a gun to my head and I hand you my wallet, we both benefit. You get my cash, and I avoid getting shot. The obvious response is "I meant mutually beneficial and *voluntary*," but the distribution of property that forces people into mutually beneficial transactions that still suck , is also not voluntary.