Mike Beggs on How a Viable Socialism Might Work (UNLOCKED)

In his essay "The Market and Workplace in a Democratic Socialism," Mike Beggs lays out out a post-capitalist vision that would avoid predictable sources of inefficiency and perverse incentives.

In my essay here last week, I wrote that my view on social democracy is that it’s a is a “nice start,” but that “the ultimate goal should be a more basic transformation of the economic basis of our society.” I had other fish to fry in that one, so I just said this and moved on, but I want to circle back to it now. I know this is the kind of thing it’s very easy to say. It’s much harder to explain exactly what it means.

Marxist sociologist Erik Olin Wright makes a useful distinction in his book Envisioning Real Utopias. We can ask about any proposal for social change first if it’s “desirable” and then if it’s “viable” and finally, if the answers are “yes” and “yes,” we can ask if it’s “achievable”—in other words, whether there’s a workable political strategy to take us from here to there.

It’s very easy to point at the numerous harms caused by markets and say “therefore we should get rid of all market mechanism and have wall-to-wall economic planning” and then, when asked exactly how this would work, to mumble something about participatory democracy and how it’s impossible to draw up exact blueprints in advance. The problem is that this convinces no one who’s thought for more than 2-3 minutes about all the ways things could go wrong.

“The calculation problem” is really a bundle of problems about how to plan an economy in a way that uses resources efficiently and coordinates production with consumer preferences. The Soviet Union, for example wasn’t completely marketless. Workers were still paid in rubles that they used to purchase goods at grocery stores. Nevertheless, these problems wreaked all sorts of havoc on the day-to-day functioning of the economic machine. There’s every reason to worry that they would be an even bigger problem for any future socialism that tried to go further than the Soviets did in the direction of truly wall-to-wall planning.

Marx could roll his eyes, in the preface to the second German edition of Capital, at the request for “recipes for the cookshops of the future.” But after the bitter experience of what used to be called “actually existing socialism” in the twentieth century (i.e. back when it actually existed), his twenty-first century successors need a better answer.

I agree that, if we help ourselves to the assumption that we can figure out how to implement a totally marketless form of democratic planning in a way that preserves both material abundance (so, no breadlines or routine shortages) and personal freedom (so, no Neighborhood Consumption Council peering over my shoulder at my shopping list), this would be more desirable than a form of socialism that preserved a role for markets.

But desirability is a different question than viability—in other words, from whether we actually do know how to implement it in a way that preserves these goods. The latter is an engineering problem, and sadly I’m not convinced that, at least at this stage of history, anyone has a plausible solution to it. Here’s economics professor and Jacobin contributing editor Mike Beggs laying out one dimension of the problem:

If we are to choose what to consume at all, the trade-offs inherent in using scarce resources must be presented to us in some way, so there will be some form of relative price and budget. It is not only that it would be cumbersome for planners to get choices from us in some other way but that we do not know ourselves the answer to questions about how many coffees we would be prepared to give up for so much extra gasoline next year. This is because our demand for any one product is bound up with our demand for other ones. The amount of coffee people would choose to consume not only depends on its own price but on many other prices, too. It would depend not only on prices of substitutes like tea or Red Bull, and complements like cigarettes and cake, but also on seemingly unrelated commodities like gasoline and housing rent — since everything must be paid for from the same budget.

Because of these connections, it takes only a handful of products to make consumer choice a fiendishly complex problem for a planner. And it is not the kind of problem that can be solved by throwing computing power at it. This is because the information we need to solve it is information about what individuals would choose given many, many different configurations of trade-offs or prices. And that is not even information that we consumers ourselves have as data to input into the computers in the first place.

And, as he goes on to note, this isn’t even to get into the original “calculation problem” about the allocation of capital goods. The more you look at it, the less tractable it all looks.

If you’ve come to grips with the calculation issues for totally marketless planning and conceded that we’ll still need a market sector in any form of socialism we know how to implement in the short term, it’s easy to think that all your viability problems have therefore been solved. You can just say, “OK, the experience of actually existing social democracy shows that sectors like healthcare and education can be nationalized and even decommodified without bad results, it’s reasonable to think ‘commanding heights’ like banking and energy belong in the state sector as well, and if we do still need a market sector for consumer goods, the firms in this sector can at least be worker-owned, thereby satisfying the core socialist goal of eliminating the division of society into a class of workers and a class of business-owners.”

In fact, I’m pretty sure I have said pretty much exactly that many times and in many contexts. I still think this is a perfectly reasonable response to 101-level worries about the “socialist calculation debate.”

But an interlocutor who really knows there stuff can push back in all sorts of ways. The incentives facing worker-owned firms aren’t identical to those facing conventional capitalist firms, and not all of the differences point in the right direction.

Mike Beggs meets that more sophisticated challenge in the essay I quoted above. It was originally published in Catalyst as “The Market and Workplace in a Democratic Socialism” and later reprinted by Jacobin as "We Can Craft a Workable Workplace Democracy for a Socialist Future.”1

He starts by acknowledging something that might surprise a lot of grassroots socialist who are unfamiliar with this literature. Some of the most thoughtful authors to have outlined proposals for “market socialism” actually give up on the goal of workers’ control of the means of production. And they don’t make this concession because of an insufficient level of enthusiasm for socialism in their souls but because of serious viability concerns.

So, for example, John Roemer’s model in his book A Future for Socialism institutionalizes egalitarian universal stock ownership, with financing for new firms financed by public banks, but he assumes that wage labor—which Marx often treats as a synonym for “capitalism”—will continue to exist. Labor markets would work pretty much the way they do know, and workers would still have to follow the orders of managers who wouldn’t be democratically accountable to them.

If you think, as I do, that this would be an absolutely disastrous concession to make—one that would destroy a giant part of the reason to want to move toward a socialist future—this is all the more reason to grapple seriously with the all-too-real problems that lead them to make this concession.

At the most basic level, Roemer motivates his caution—as Mike says, Roemer is “agnostic at best” about labor management—with a biological metaphor. “[A]n organism with one mutation is more likely to survive than one in which two mutations occur simultaneously.” Equalizing wealth and thus having to find an alternative way to finance firms is a big enough mutation on its own, at least as a “first step.”

Mike concedes that there’s more than nothing to this concern. But he wants to “push further down the road to utopia, while trying not to actually be utopian by ignoring predictable problems.”

One of those problems is that the socialist goal of workplace democracy—at least as realized through independent worker-owned firms—is in tension with the socialist goal of distributive egalitarianism. Matt Bruenig, for example, has emphasized this as an objection to Richard Wolff’s “coop socialism.” A private sector of worker-owned firms wouldn’t give rise to the kind of staggering inequality whereby Jeff Bezos can buy his own spaceship and a lot of the people who work in his warehouses have to get second jobs, but there would still be significant inequalities between firms. Some industries are just vastly more profitable than others, for example because of what kind of capital inputs they require, and Matt worries that, however you try to structure this kind of socialism, you’ll “wind up with really unacceptable levels of inequality.”

Another predictable problem Mike Beggs acknowledges is what economists who study labor-managed firms call the “common-property problem”:

Democratic firms have less of a drive toward expansion than capitalist ones: the need to share all profits with new members means that incumbents have no incentive to expand once increasing returns to scale have been exhausted.

Wisely, he doesn’t try to argue that his proposal makes either problem entirely disappear.

Absolute utopia isn’t on the table. If you want to completely eliminate markets, you get (currently intractable) calculation headaches. If you want to retain a role for markets, you get some degree of income inequality that would go beyond what would be permitted by a philosopher’s notion of perfect justice in distribution. (Innate talents, for example, are unevenly distributed throughout the population, and the more talented are going have more bargaining power, which is central to G.A. Cohen’s case against markets.) If you want to Roemer-ishly retain both labor markets and commodity production—i.e. the exact combination Marx spends Capital arguing is the problem with capitalism!—you jettison a good deal of the original motivation for the socialist project. If you concede the need for what Mike provocatively calls “socialist commodity production” while seeking to at least move beyond capitalist labor markets, the problems identified above rear their heads. There’s no option that doesn’t create trade-offs. The question, when it comes to writing an appealing recipe for socialism’s cookshops, is whether we can at least devise a model that shrinks whatever set of problems we end up with down to a manageable size while maintaining the benefits on the other side of the ledger.

To this end, he starts by assuming a society that, much like the one we live in, has a “public sector” and a “private sector.” Under actually existing capitalisms, the line between the two can be blurry, and in his kind of socialism, it would get even blurrier, but the terminology is reasonably clear and convenient, so he retains it.

The “private” sector would consist of worker-owned “collectives.” (My sense is that Mike uses this term to differentiate the firms he’s imagining from actually existing “worker cooperatives,” which are what you get when you combine workplace democracy with the rules of regular capitalist markets.) Depending on the size of the firm and the technical knowledge required to efficiently manage it, workers would either directly elect managers or elect the workers’ council in charge of hiring and firing managers. They would also vote for “operating agreements” that would be a bit like a unilateral version of union contracts.

Shares of the collectives aren’t bought and sold. You get your vote and your cut of the revenue when you join the firm and lose it when you leave, just as I get my vote in Los Angeles City Council elections and my access to city services when I move to LA and lose these things when I go somewhere else.

The public sector would be larger (in the sense of providing more services) than in any capitalist nation, and perhaps also larger in terms of its share of total employment (which would help ameliorate the concern about hiring incentives). Mike suggests, for example, that many kinds of intellectual property protections could be removed in favor of state financing of intellectual and artistic creation, and inheritance abolished in favor of the savings of the dead being redistributed in an egalitarian way to the living—thus eliminating a crucial source of economic inequality.

Crucially, as in Roemer’s model, the banking sector would move into the public realm. People could park their savings there and earn interest like they do from regular capitalist banks, but they would have no private owners. The primary mechanism for both starting new firms and expanding old ones would be grants from these public banks—and firms with a wage-labor model need not apply. In practice, the socialist state would be a partner in every “private” firm.

While there could certainly be a role for a few development banks for politically important purposes like promoting green technology or reindustrializing areas devastated by late-stage capitalism, for the most part the public banks would be semi-autonomous and kept “at arm’s length” from policy in order to avoid the kind of “soft budget constraints” making it politically impossible to let inefficient firms go under that plague some other socialist models. If you’re turned down at one semi-autonomous bank you can try your luck at another. Firm failure would continue to exist, although given the price of failure wouldn’t be destitution but embarrassment and having to deal with more skeptical grant officers at the public bank next time you have a bright idea for a new collective. These officials’ careers, and the funding level for their bank, would depend on their ability to secure a good return on their investment.

This return would, as in the similar model proposed in David Schweickart’s book After Capitalism, take the form of grant payments that can be thought of either as a kind of special tax or as a loan payment where the collective is only paying off the interest and not the principal. In essence, the state owns the physical means of production and rents them out to collectives. The rate of this rent, as a matter of policy, can vary by industry, which can help ameliorate the problem about firm-level inequality. The banks would also be incentivized to “identify niches where new collectives could thrive and play an active role in assembling people in search of work,” which can help ameliorate the common-property problem with new hiring.

For a few reasons, including both technical concerns about incentivizing collectives to adopt more efficient technology and more familiar socialist concerns about mitigating market pressures on workers to push their earnings down to a point that starts to look like “self-exploitation,” public labor boards (for which there are interesting precedents under capitalism in, for example, “postwar Australia and Scandinavia”) set benchmarks for the incomes of worker-owners in every industry. Firms that couldn’t pay their members at this benchmark would be considered insolvent. But of course they have every incentive to generate revenue that could be paid out beyond the benchmarks. Workers are the residual claimants for this revenue when everyone else has been paid off. The collectives “do not accumulate wealth — they are custodians of capital, not owners.” Expansion is driven by expansion grants, which mitigates another of the perverse incentives that’s supposed to afflict worker-owned firms—the “horizon problem” whereby older workers or workers with one eye on a change of career wouldn’t be willing to sacrifice existing income to pay for expansion that might not pay off until they leave the firm. And, beyond the standard mechanisms of a maximalist social-democratic welfare state—a theoretical construction sometimes called Slightly Imaginary Sweden, which would be the jumping off point for this vision of socialism—the inegalitarian effects of differences in firm revenue would be offset with a substantial Universal Basic Income generated by the earnings of public banks.

Under capitalism, most adults who directly participate in the economy earn most of their income from wages, often supplemented by some stock ownership (through, for example, retirement savings). Under this version of socialism, worker-owners in the “private” sector would have three sources of income (while those in the more stable public sector would have only the fist and the third):

(Regularized) labor income—what they get from their regular paycheck from the collective, where the floor is set by the Labor Board’s benchmarks and the ceiling is whatever makes sense given the democratically determined firm strategy

Their less predictable share of remaining firm revenues after all other claimants (including themselves in their role as recipients of regularized labor income) have been paid off

UBI payments from the public purse

Mike also has a lot of plausible things to say about macroeconomic policy, how public financial institutions could manage risk, and the like. My summary here is no substitute for reading his (much longer) essay. He certainly doesn’t claim that there are no tradeoffs of any kind here. But he does paint what I regard as a deeply appealing vision of what a realistic socialism could look like in the historical near term.

Here’s how I’d understand the point:

He’s not trying to write a recipe we expect anyone to follow in the cookshops of the future. As he says in the essay, “nothing would force” the citizens of a future socialist society “to use our recipes if they no longer suit the tastes or solve the problems of the time.” Nor is any of this offered as the endpoint for future social progress. If we can solve the engineering problems identified above, we should obviously do it.

Instead, the point is a very simple one.

It’s important to be able to offer a sample recipe that uses ingredients that have already been invented, rather than ones we have faith will come into existence by the time we need them, if we want to demonstrate that the people who show up at our cookshop aren’t going to starve.

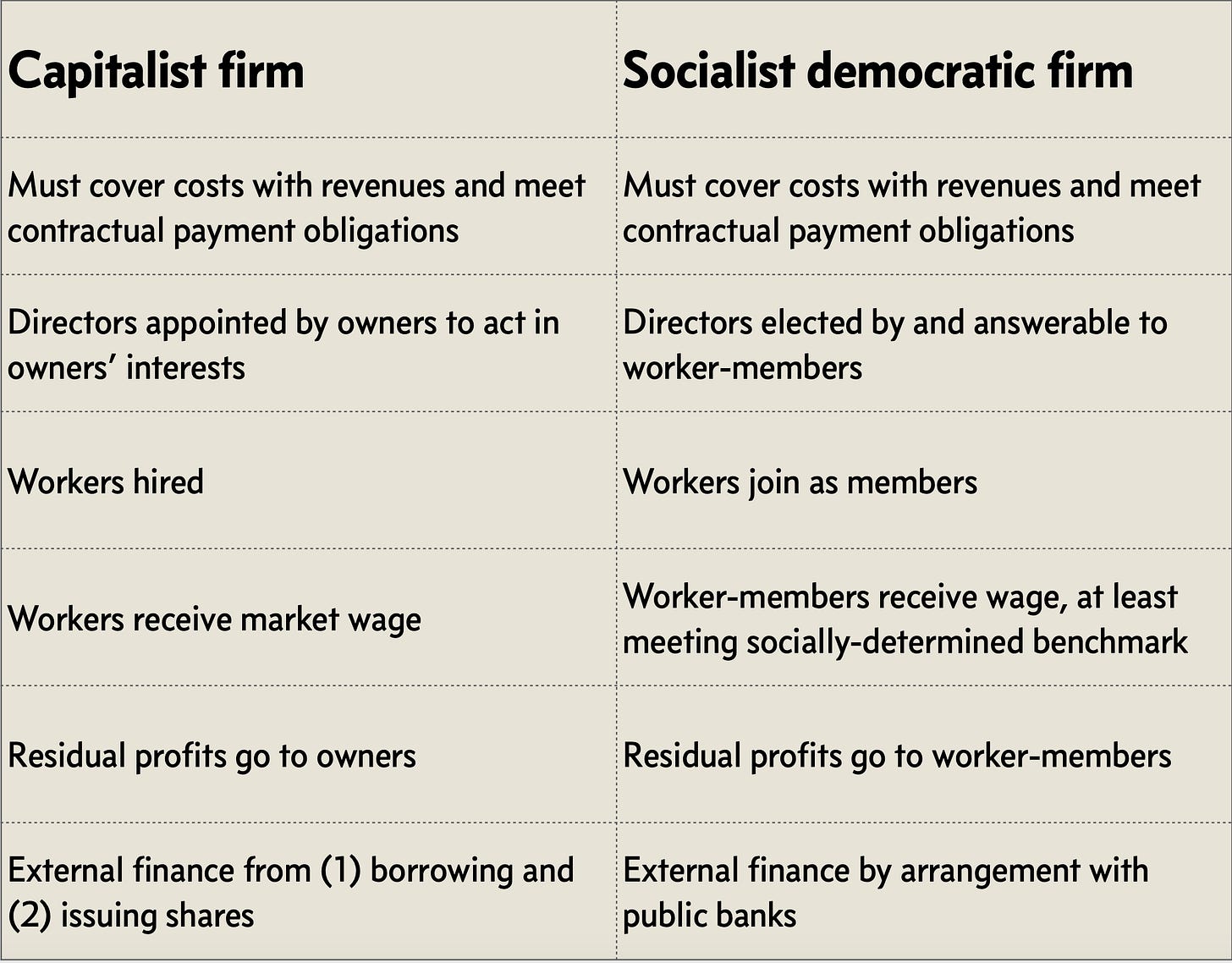

Note: The table above is taken from Mike’s presentation last year at the Socialism conference in Chicago.

Full disclosure: I’m co-writing a book with Mike and our friend Bhaskar Sunkara expanding on what he says in this essay. That one might be coming out from Verso as early as next year!