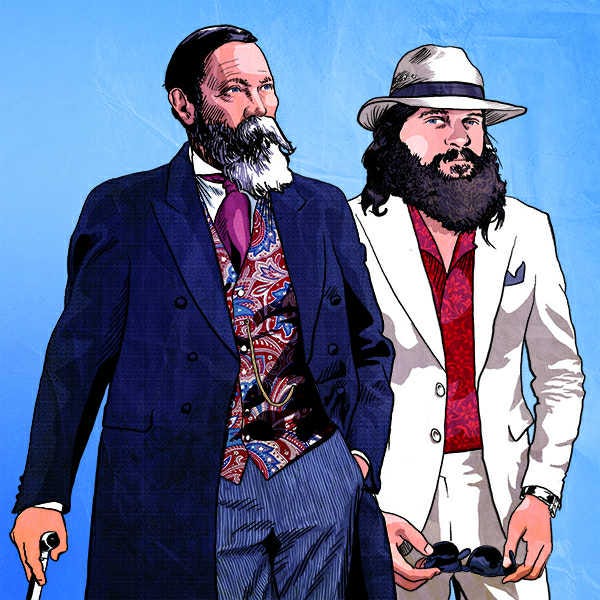

Engels and Marx as Philosophical Comrades

Engels is often treated as, at best, a kind of intellectual sidekick to Marx. But, as Sam Badger explains in this guest essay, Engels played a major role in developing what we now know as "Marxism."

This guest essay was kindly contributed by Sam Badger. You can (and should) read him at his own Substack, where he covers philosophy and socialist politics.

In the mainstream intellectual history of Marxism, Karl Marx was the great genius and Friedrich Engels was a sort of philosophical sidekick who was around to edit Marx’s works and occasionally bounce off ideas with. There is a kernel of truth to this reading, and it is one which Engels himself endorsed in his eulogy to his friend in Highgate Cemetery. Engels’s main goal after Marx’s death was to disseminate Marx’s ideas, edit the two remaining volumes of Capital for publication (as well as a few other previously unpublished works such as the “Critique of the Gotha Program”), and interject himself polemically in socialist politics.

Other intellectual histories take a different approach by denigrating Engels as a kind of amateurish figure whose simplistic understanding of Marxism led to everything from Stalinist autocracy to economic determinism to ecological devastation. In this reading, there is a kind of esoteric Marx that was concealed thanks to the intellectual crudity of Engels. It is not unlike those neo-gnostics who argue that Paul ruined the pure Christianity of Jesus. The latest example is Kohei Saito’s work Marx and the Anthropocene, which accuses Engels of ignoring Marx’s increasing concern with ecology.1 In Saito’s interpretation, Marx made a “turn” away from class conflict and towards the exploitation of nature. Saito argues that Engels missed this, and that the Marxism propagated by Engels after Marx’s death disregarded ecological sustainability in favor of perpetual growth.

Both of types of narrative are deeply unfair to Engels. Most importantly, they miss the significant influence which Friedrich Engels had on Karl Marx. Neither of these interpretations see Engels from Marx’s point of view, and ask the question, why did Marx rely on Engels so much if he was simply a sidekick, or worse, the vulgarizer of the whole tradition? The fact that Marx trusted Engels as a confidant, ally, and editor is evidence enough that Marx himself didn’t consider Engels’s contribution to be so secondary. On the contrary, later in life we see Marx trusting Engels with important tasks like attacking the reactionary socialism of Eugen Dühring in his appropriately named Anti-Dühring (as well as the authoring of a shorter pamphlet based on the work, Socialism: Utopian and Scientific). Moreover, even if Engels himself never got a doctorate, arguably working alongside Dr Marx for decades might as well be a de facto dissertation.

Marx’s respect for Engels as a socialist thinker and activist emerged not long after their first meeting in the 1840s. When Marx first met Engels, he was not particularly wowed by the young bourgeois German. Yet after their first meeting, in 1843 Engels submitted his article “Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy” to the paper Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, of which Marx was the editor.2 Only two years later, Friedrich Engels published his first book The Conditions of the Working Class in England. These two works impressed Marx and deeply influenced his later thinking.

The importance of Engels’s “Outline” of capitalism

Engels’s modest article “Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy” has an apt title. The work lays out the structure of the emerging industrial market economy, and critiques English liberal economics as “a system of licensed fraud, an entire science of enrichment” from the earlier epoch of “elementary, unscientific huckstering”. Engels takes on the theoretical system built up through the works of Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus, David Ricardo, and James Mill, as well as the practices which these theories sought to describe (and justify).

Notably, Engels does not simply attack the liberal political economists. Rather, he accepts the contingent truth and utility of their thinking, at least for the bourgeoisie. It makes sense that Engels, as a young member of the bourgeoisie working in his father’s textile enterprise, would understand what capitalists saw in Smith’s Wealth of Nations. If we put it in pragmatist terms, bourgeois economic theory was more or less adequate for the world they inhabited. Yet Engels aimed to turn political economy against itself and reveal its dark side. Where competition appears to the bourgeoisie as a way to keep down prices and improve quality, this is only true for those with bargaining power. Those without bargaining power – specifically, the working class – have a much different experience with competition. Rather, competition drives down the price of their labor, deepens their immiseration, and forces them into the “surplus population”.

What’s interesting about the essay is how it anticipates Marx’s Capital. At the time which Engels wrote this essay, Marx was wrestling with Hegelian philosophy and political economy in his 1844 Manuscripts. This early work was never published, and may not have ever been intended for publication. The “Outline” is closer to the content of Marx’s later Capital in taking on English political economy head-on. Where Marx’s 1844 Manuscripts develops concepts that can be found in the background of Capital like alienation, Engels’s “Outline” contains the concepts that are front and center in Capital.

Perhaps the most obvious example is how Engels anticipates Marx’s explanation of the way in which the commodity as an object necessarily contains both exchange value and use value. As Engels explains, the value of utility is qualitative and subjective, while the value of exchange is quantitative and objective. Capitalist production presupposes that the utility can justify the cost of production (and when this presupposition is wrong, businesses might go bankrupt):

Let us try to introduce clarity into this confusion. The value of an object includes both factors, which the contending parties arbitrarily separate – and, as we have seen, unsuccessfully. Value is the relation of production costs to utility. The first application of value is the decision as to whether a thing ought to be produced at all; i.e., as to whether utility counterbalances production costs. Only then can one talk of the application of value to exchange.

Marx would take this idea and run with it. As Marx explains, commodities have a dual nature, being defined by both their exchange-value and use-value. This ties into his concept of a commodty “fetish.” The material object contains both its material utility and its immaterial value, much as the religious fetish is both a mere statue and also a powerful deity.

Over the course of his outline, Engels identifies many of the other concepts which loom large in Marx’s Capital, such as theories of overpopulation, unemployment, and the way competition pushes monopolization. Though he does not systematize these concepts, he does not want to. He’s merely offering an outline, and it’s an outline that Marx fills in over his three volumes of Capital. Sure, there is much which is not there yet, but Engels provides Marx with the basic concepts he needs to begin this project.

Engels’s Conceptual Influence

Engels wrote his Conditions of the Working Class in England between the ages of 22 and 25, and he exhaustively details the suffering of the English working class and the Irish immigrants living among them. He did this despite being a foreigner in their land, and despite most of the sources being in his second language. The book is notable for its reliance on empirical information, official statements, and Engels’s own first-hand journalistic reporting. The first chapter begins with his description of his voyage into an industrializing and bustling London, before moving on to a meticulous description of the working-class neighborhoods in Manchester. He details the poor drainage, bad air, cramped quarters, and bad sanitation and connects these to effects like the ever-worsening cholera epidemics in the city. He also clearly takes an attitude of indignation towards the wealthy, and empathy towards the poor.

We can quickly recognize some of the concepts of Capital in Engels’s earlier work. In one example, Engels understands that the value of labor (whether it is the one hundred men or the one) is based on the value of subsistence:

If the workers are accustomed to eat meat several times in the week, the capitalists must reconcile themselves to paying wages enough to make this food attainable; not less, because the workers are not competing among themselves and have no occasion to content themselves with less; not more, because the capitalists, in the absence of competition among themselves, have no occasion to attract working-men by extraordinary favours.

The value of the worker is his cost of subsistence, which means food, drink, housing, education, coffee, and anything else which he needs to wake up in the morning and go to work. This value is determined normatively, as workers in more prosperous societies might enjoy “necessities” those in poorer societies do not (like smart phones, or in Engels’s example, meat). Engels sees that the egoistic profit motive drives industrialization to reduce the labor cost, and that this drives a boom and bust cycle of crises that causes unemployment.

Engels’s Methodological Influence

Engels’s influence is not only conceptual but methodological and rhetorical. Notably, Engels pioneered a method which would be taken up by Marx in Capital. This is the liberal use of citations from English bourgeois regulators, surgeons, medical examiners, and lawyers about the terrible conditions of the workers and the rank hypocrisy of the capitalists.3 This citation serves a double purpose. First, it provides raw evidence for their conclusions from a relatively unimpeachable source. Simply put, both Engels and Marx needed to provide meat to their claims that workers were suffering. These citations turn the abstract mechanics of political economy into real stories of people’s suffering. Second, it serves a rhetorical purpose by showing how even members of the bourgeois establishment recognize the problem. These sources have no motive to lie, or if they do would be motivated to lie in the other direction. Rather, they are horrified by what they witness in workplaces. Even if they presume the logic of market capitalism as natural or inevitable, they clearly and unequivocally moralize against the effects which Marx and Engels predict.

Perhaps the most notable example of this from Marx’s Capital is his extended description of the death of Mary Ann Walkley, a seamstress who died after a 26 ½ hour workday sustained by coffee and alcohol in a poorly ventilated room with many other women. Marx recounts her story in detail, before citing the medical examination by Dr Keys which attested to the cause of her death as follows:

“Mary Anne Walkley had died from long hours of work in an over-crowded work-room, and a too small and badly ventilated bedroom.”4

In a footnote on the same page, Marx provides a citation to one Dr Letheby describing the awful, cramped working conditions. He is nothing if not thorough in wanting you to know the medical consensus on her fate.

If one takes a look at Conditions of the Working Class, it becomes clear where Marx got this idea of citing surgeons when he spends several pages detailing the health effects of long working hours on children. If anything, he gets a bit overly excited in this by citing a whole panoply of doctors in his chapter on factory workers. In one example, he cites one Dr Francis Sharp on the bone deformations of working class children:

Before I came to Leeds, I had never seen the peculiar twisting of the ends of the lower part of the thigh bone. At first I considered it might be rickets, but from the numbers which presented themselves, particularly at an age beyond the time when rickets attack children (between 8 and 14), and finding that they had commenced since they began work at the factory I soon began to change my opinion. I now may have seen of such cases nearly 100, and I can most decidedly state they were the result of too much labour. So far as I know they all belong to factories, and have attributed their disease to this cause themselves.”“Of distortions of the spine, which were evidently owing to the long standing at their labour, perhaps the number of cases might not be less than 300.

In this way, Engels can take the abstract economic principles and economic mechanisms like competition and finds that they appear in the very skeletons of working class children.

One important difference between Engels’s early work and Marx’s three volumes of Capital is that they are far more interested in the moral problems of capitalism. Engels describes the atomistic egoism inherent in capitalism, how competition both presupposes and justifies this egoism in a vicious cycle, and how it drives a process of degeneration (or “demoralization”) of the workers. Though Capital does return to this theme, and is not without normative claims, it is ultimately a scientific work. Engels’s early work is rather both a proto-sociology of the suffering of the workers and a moral polemic against its causes. This is why Engels spends a considerable amount of time describing the phenomenon of “social murder”, which is to say the wrongful and unnecessary waste of human life by alien and inhuman social systems.5 Marx does take time to defend the moral claims of the working class like his ringing endorsement of the “modest Magna Carta” of the legally limited working day. Yet overall, Marx is much more interested in the economic mechanisms than he is in a moral condemnation of the capitalist class.

Dialectics, Empiricism, and Historical Materialism

If Engels made a deeper contribution to Marx’s theory, it is the way he bridges the abstract theory and the empirical, material history of society. Of course, Marx was a journalist too before meeting Engels, and he had written his share of empirical work. Yet Engels’s Conditions of the Working Class seems to have been an early paradigmatic example of how to do this well.

What made Engels’s approach so compatible with Marx’s is, ultimately, their shared philosophical baggage. Both were steeped in the Hegelian tradition as well as English political economy (something Hegel himself was steeped in). Yet they both agreed that to be of any use, Hegel had to be turned “on his head”. Hegel’s idealistic dialectic viewed history as the self-motivated unfolding of spirit in history. Spirit was understood as the historical development of thought, as people’s ideas became more consistent with reality. Hegel thought that seemingly opposed things like “mind” and “body” or “being” and “nothing” are merely parts of some abstract, conceptual totality. Instead of situating that dialectical process in the development of our thoughts, Marx and Engels situated it in the system of material production and reproduction. This meant that theoretical truth must be reflected in the content of our experience, our relationships to one another, and our relationship with nature. In this way, the dialectic described by Marx and Engels was characterized as materialist, and therefore also something that can be seen empirically.

Though they do look to the empirical more than Hegel did, Marx and Engels both reject the kind of empiricism that characterized Anglo-Scottish political economists like Adam Smith and Thomas Malthus. English philosophy is right to turn its gaze towards the world and observe its content, but their observations tend to be uncritical. Malthus, for instance, observes the fecundity of the working class and extrapolates that this will lead inevitably to a population crises. Yet Engels criticizes this claim for its unquestioned assumptions (that agricultural production increases linearly) and ahistorical approach which led Malthus to miss that overpopulation was merely a symptom of a particular historical condition. Malthus takes what he sees at face value and uses that as the basis for his thinking, without ever questioning whether what he sees is historically contingent. He does not consider whether the concepts he uses to interpret this might be biased by his class background or his historical moment. Rather, he just sees workers having lots of kids, unemployment, and a potential shortage of agricultural land and infers that overpopulation must be a law of nature.

Engels and Marx, Intellectual Comrades!

All this is to say, if one looks at the stylistic, rhetorical, and argumentative analogies between Engels’s Conditions of the Working Class and Marx’s later Capital, it becomes apparent that the former work was a model for the latter. It was an example of how one could situate a Hegelian dialectic within the historical process, and find concrete empirical evidence of the theory of class struggle. This gets us away from the readings of Engels as a mere vulgarizer or mere editor of Marx’s works, or some other notion that puts him as a kind of second fiddle to the “great genius”. None of this is to say that Engels was the great theorist either. Marx did go beyond Engels, but only because Marx saw what the young bourgeois prodigy had to offer.

Notably, the examples here just scratches the surface. A complete review of how Engels’s early writings influenced Marx would be much longer. There are many examples of how Conditions of the Working Class influenced Capital that aren’t discussed here. Yet what is clear is that Engels was no philosophical fool, and Marx respected him for a good reason. They were intellectual comrades, and Marxism is the collaborative endeavor of both!

Saito, Marx and the Anthropocene 45-51. Notably, Saito’s work doesn’t completely dismiss Engels, and this narrative has a spectrum between “Engels is a total worthless dunce” and “Engels got most things right but missed this one really important bit”. Yet what it shares is an attempt to find some esoteric truth in Marx that Engels somehow missed, and then an attempt to show how this error caused all sorts of harm to the socialist movement.

As Jürgen Herres explains; “with his [Engels’s] essay Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy – which appeared in 1844 in the Franco-German Yearbook, edited jointly by Arnold Ruge and Karl Marx in Paris, and which strongly influenced Marx –he became the first representative of the German philosophical Left to enter the field of political economy and to draw attention to the contradictions associated with the concept of private property. (Herres, in The Life, Work, and Legacy of Friedrich Engels, edited by Illner et al., 2023

In footnote 15 in chapter 10 of Capital, Marx makes clear how he builds upon the earlier analysis of Engels: “I only touch here and there on the period from the beginning of modern industry in England to 1845. For this period I refer the reader to “Die Lage der arbeitenden Klasse in England,” [Condition of the Working Class in England] von Friedrich Engels, Leipzig, 1845. How completely Engels understood the nature of the capitalist mode of production is shown by the Factory Reports, Reports on Mines, &c., that have appeared since 1845, and how wonderfully he painted the circumstances in detail is seen on the most superficial comparison of his work with the official reports of the Children’s Employment Commission, published 18 to 20 years later (1863-1867). These deal especially with the branches of industry in which the Factory Acts had not, up to 1862, been introduced, in fact are not yet introduced. Here, then, little or no alteration had been enforced, by authority, in the conditions painted by Engels. I borrow my examples chiefly from the Free-trade period after 1848, that age of paradise, of which the commercial travellers for the great firm of Free-trade, blatant as ignorant, tell such fabulous tales. For the rest England figures here in the foreground because she is the classic representative of capitalist production, and she alone has a continuous set of official statistics of the things we are considering.”

“When one individual inflicts bodily injury upon another such that death results, we call the deed manslaughter; when the assailant knew in advance that the injury would be fatal, we call his deed murder. But when society places hundreds of proletarians in such a position that they inevitably meet a too early and an unnatural death, one which is quite as much a death by violence as that by the sword or bullet; when it deprives thousands of the necessaries of life, places them under conditions in which they cannot live – forces them, through the strong arm of the law, to remain in such conditions until that death ensues which is the inevitable consequence – knows that these thousands of victims must perish, and yet permits these conditions to remain, its deed is murder just as surely as the deed of the single individual; disguised, malicious murder, murder against which none can defend himself, which does not seem what it is, because no man sees the murderer, because the death of the victim seems a natural one, since the offence is more one of omission than of commission. But murder it remains. I have now to prove that society in England daily and hourly commits what the working-men's organs, with perfect correctness, characterise as social murder, that it has placed the workers under conditions in which they can neither retain health nor live long; that it undermines the vital force of these workers gradually, little by little, and so hurries them to the grave before their time. I have further to prove that society knows how injurious such conditions are to the health and the life of the workers, and yet does nothing to improve these conditions. That it knows the consequences of its deeds; that its act is, therefore, not mere manslaughter, but murder, I shall have proved, when I cite official documents, reports of Parliament and of the Government, in substantiation of my charge” https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/condition-working-class/ch07.htm

Your piece is interesting and lucid. I also feel reinvigorated thinking about the potency of Marxism as explanation. Boy, do we need it.

Thank you for giving me fun things to think and read about!