Did Rawls Kill Analytical Marxism? (UNLOCKED)

Joseph Heath says so in his essay, "John Rawls and the death of Western Marxism." But the core of his argument makes very little sense.

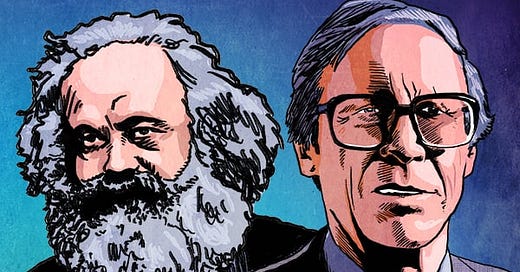

In his essay “John Rawls and the death of Western Marxism,” Joseph Heath writes that when he was an undergraduate “by far the most exciting thing going on in political philosophy was the powerful resurgence of Marxism in the English-speaking world,” following “the publication of Gerald Cohen’s Karl Marx’s Theory of History: A Defence” in 1978 and the beginnings of “analytical Marxism.”

One could say, without exaggeration, that many of the smartest and most important people working in political philosophy were Marxists of some description. So what happened to all this ferment and excitement, all of the high-powered theory being done under the banner of Western Marxism? It’s the damndest thing, but all of those smart, important Marxists and neo-Marxists, doing all that high-powered work, became liberals.

Oh no, liberals!

But…what does that mean?

“Liberalism” sometimes designates a political position to the right of socialism or even robust social democracy but to the left of conservatism or libertarianism. In the contemporary American context this part of the spectrum tends to be occupied by forces that emphasize an unappetizing blend of identity politics and technocratic tinkering with the status quo.

Alternately, “liberalism” can refer to a belief in the importance of “liberal rights” such as freedom of speech. When some position or faction is called “illiberal,” this is the “liberalism” they typically stand accused of rejecting.

If the context is a seminar on the history of philosophy, “liberalism” can mean a third thing—a basic commitment to human equality. The idea that we’re all born with the same moral status was pretty heady stuff in the eighteenth century but these days only the strangest reactionaries—think Yarvin, think Dugin—openly reject “liberalism” of this kind. Everyone else just argues about which rights we all have.

And rounding out the taxonomy, some libertarians and libertarian-adjacent right-wingers reserve the l-word for themselves, insisting that they and not the first-category progressive technocrats are the “true liberals.” Think of Reason magazine’s slogan “free minds and free markets.”

Putting all that together, we’ve got:

Liberalism #1: Liberalism as a position on the political spectrum

Liberalism #2: Liberalism as a commitment to "liberal rights”

Liberalism #3: Liberalism as a broad philosophical position centering on moral universalism

Liberalism #4: Free-market liberalism

So, when Heath says that Cohen, for example, “became” a “liberal,” which of the four does he have in mind? It can’t be 1 or 4, because Cohen died a fiercely committed socialist. So for example, did Erik Olin Wright, probably the second-most important “analytical Marxist.”

It can’t be 2 since Cohen was always very clear on his support for “liberal rights” (for example, whenever he talked about Stalinism). Nor does 3 look promising. Famously, Cohen said that reading Nozick’s 1974 Anarchy, State & Utopia awoke him from his “dogmatic socialist slumber.” He’d previously assumed that any halfway plausible moral theory would entail support for socialism. So, there was no need for socialist philosophers to bother with normative work. Now, he realized that the libertarian attack required a strong defense and counterattack. This all happened a few years before the first edition of Karl Marx’s Theory of History.

Heath clarifies:

Of course, this was not a capitulation to the old-fashioned “classical liberalism” of the 19th century, it was rather a defection to the style of modern liberalism that found its canonical expression in the work of John Rawls.

Perhaps the “liberalism” he has in mind, which we can call Liberalism #5, is just “agreeing with Rawls.” Certainly Rawls makes a big point of calling himself a “liberal,” although what he had in mind was definitely Liberalism #2, and his point in using that term was to emphasize the continuity between what he was saying and the insights of historically important “liberals” like Kant.

Importantly, though, Rawls wasn’t committed to Liberalism #1. He was often read as a political-spectrum liberal but in A Theory of Justice he goes out of his way to remain agnostic about capitalism vs. socialism. His view was that this debate boiled down in large measure to empirical questions about the effects of the systems that couldn’t be settled from the philosophical armchair. And when, late in his career, he finally moved away from this agnosticism (in a famously slow and “recalcitrant” way), he broke against Liberalism #1. In Justice as Fairness: A Restatement, he decides that capitalism, even when softened with welfare-state mechanisms, can’t meet the requirements of his theory of justice, and neither for different reasons can Soviet-style authoritarian state socialism. Reluctant to the end to take definite political stands, he offered not one but two possible social arrangements that could meet his test—”liberal socialism” and “property-owning democracy.”

The first just means a form of socialism that would be consistent with Liberalism #2—so, what someone like Cohen advocated throughout his career. The second is far vaguer idea, but core of it seems to be that ownership of the means of production wouldn’t be collective but it would somehow be so diffused throughout the population that there would no longer be a meaningful class division between workers and capitalists.

If what Heath means is that Cohen—the figure he spends the most time on—started out as a Marxist and “became a liberal” in the sense of Liberalism #5 (agreeing with Rawls), there are two big problems with that claim. One is that Liberalism #5 is entirely consistent with Marxism. The other is that Cohen devoted quite bit of his philosophical energy in the last stage of his career to critiquing Rawlsianism from the left. Rawls’s view is that, while inequalities in the distribution of resources are presumed guilty and need to be proven innocent, they can redeem themselves if they’re necessary for providing incentives for economic contributions that work to the net benefit of whoever gets the short end of the stick. Cohen thought that inequalities of this kind could still be unjust.

I explore that debate here. All I’ll add now is that a socialist could side with Rawls without contradiction to her commitment to bringing about a more equal society by expropriating capitalist property. The Soviet economy, for example, had a narrower range of income inequality than capitalist countries, but they didn’t have completely flat payscales, and a more democratic form of “full socialism” likely wouldn’t either. Actually existing worker coops don’t have anything like the staggering internal inequalities of capitalist firms where a CEO might make hundreds or thousands of times the income of an average worker, but they still feel the need to incentivize people to take certain jobs by offering higher salaries.

But while a socialist could accept Liberalism #5, Cohen didn’t. He thought that some tradeoffs between egalitarian justice and economic efficiency might be necessary at given stages of history, but we shouldn’t lose sight of what’s being traded way.

As it happens, I think Cohen has a point about this. But regardless of who’s right here, the crucial point here is that there isn’t the slightest incomptibility between Rawls’s theory of justice (or some even-more-egalitarian alternative) and Marx’s theory of history. Given the fact/value distinction, there’s simply no way for such an incompatibility to get off the ground. Marx’s historical materialism is a theory about how different modes of production (such as feudalism, capitalism, and socialism) work, and how and why they rise and fall over the course of history. Rawls’s theory of justice is a theory about how to normatively evaluate different possible or actual societies. Thinking the two are incompatible is like saying that “the mug I’m drinking this coffee out of is cold” is logically inconsistent with “there’s a Rolling Stones tongue-and-lips logo on the side of the mug.”

Marx was no moral philosopher, and perhaps even thought moral philosophy was a waste of time, but he constantly expressed moral reactions to various possible or actual social arrangements. Anyone who’s so much as skimmed Capital knows Marx fairly oozes disapproval of the extraction of surplus labor time by different kinds of exploiters in feudal, slave, and capitalist systems, and that he looks with vastly more favor on the hypthetical society of “associated labor” he previews at the end of Ch. 1. And of course a Marxist-Rawlsian could easily say that both collective ownership a la “liberal socialism” and diffused ownership a la “property-owning democracy” would be just, but given the material development of the forces of production at this point in history, and the general unrealisticness of any society collectively deciding to roll that wheel backward and accept a life of voluntary simplicity, collective ownership is on the table of historical possibility and diffused ownership is not.

In fact, that’s pretty much exactly what Marx does say in the big revolutionary conclusion at the end of Ch. 32, capping off his discussion of “so-called ‘primitive accumulation’” in the early stages of English capitalism when peasants were driven off their land without “a farthing of compensation.” There’s no going backward to a bygone idyll of rural small-holding, but we can go forward to the “expropriation of the expropriators.”

Heath says several things that make it sound like he thinks that what makes Liberalism #5 a departure from Marxism is that, even if Cohen and his compatriots didn’t agree with all the details of Rawls’s theory, they came to share Rawls’s preoccupation with equality. Now, the idea that concern about economic equality is a distinctively “liberal” preoccupation, such that socialists who talk about equality therefore become more like liberals, strikes me as extremely odd on its face. That concern would seem to fall into what nineteenth-century revolutionaries called the “social question” as opposed to the “political question” of achieving democratic rights within the state. One might think that, if anything, someone like Rawls taking material inequality seriously a source of injustice reflects the political winds of socialism making themselves felt in the views of liberal philosophers.

Heath’s idea seems to be that Marxists “became liberals” when they started spending a lot of time thinking about achieving equality because if they’d stayed Marxists they would have stayed focused on overcoming exploitation.

But there’s no reason anyone should have to choose between caring about inequality and caring about exploitation. The two go hand in hand.

Heath writes:

The most natural way to specify the wrongness of exploitation is to say that workers are entitled to the fruits of their labour, and so if they receive something less than this, they are being treated unjustly. (This is why Marxists are wedded to the labour theory of value – because it makes this normative claim seem intuitively natural and compelling.)

But as Nozick observed, if this is your view, then you can’t really complain about certain economic inequalities, such as those that arise when individuals with rare natural talents are able to command enormous economic rents for their performances (this is the famous “Wilt Chamberlain” argument in Anarchy, State and Utopia). Furthermore, taxing away any part of this income looks a lot like exploitation.

But Marx emphatically does not believe that it’s unjust or wrong or bad for workers to receive less than the full fruits of their labor. In fact, in the Critique of the Gotha Program, he explicitly argues that workers under socialism wouldn’t and shouldn’t get those full fruits, since they’d need to democratically impose “deductions” on themselves to provide for the upkeep and development of the physical means of production, to provide for common needs like schools and hospitals, and to provide a living for those too young, too old, or too disabled to be reasonably expected to work. He obviously doesn’t think any of that’s “exploitation.” Rather, exploitation is the extraction of hours of unpaid labor from the immediate producers (workers under capitalism, serfs under feudalism, slaves in slave systems) without their democratic consent—whether by direct compulsion under slavery and feudalism or by existing property arrangements giving rise to the “dull compulsion” of material necessity under capitalism.

Heath goes on to say that Cohen “wrote two entire books trying to work out a response to Nozick, none of it particularly persuasive.” This is, I’m sorry, nonsense on stilts. Cohen’s response to Nozick is so thorough and decisive that by the time he’s through with him there’s simply nothing left. And, though Heath strongly suggests otherwise, Cohen never seems to have retracted a word of it.

In Heath’s story:

This led Cohen to the realization that, when push came to shove, he cared more about inequality than he did about exploitation, because how we relate to one another as human beings is fundamentally more important than our right to exercise ownership over every last bit of stuff that we make. So he switched foundations and became an egalitarian (and – though he would have hated the description – a liberal).

So nowadays, when kids like Freddie deBoer come along insisting that “Marxism is not an egalitarian philosophy,” I nod my head in agreement, but I want to respond “Yes! That’s why nobody is a Marxist any more.”

Even putting aside Marx’s explicit rejection of “our right to exercise ownership over every last bit of stuff we make,” this is just wrong. I’m a big fan of Freddie deBoer’s work in general but in this particular case I think he misses the boat. If you follow Heath’s hyperlink to deBoer, you’ll find deBoer justifying his claim that Marx rejected egalitarian considerations with a hyperlink to that same chapter of the Critique of the Gotha Program we’ve already looked at.

What Freddie is presumably thinking of is that Marx critiques the Lassallean faction of the German socialist movement for saying that each worker under socialism should “equally” get the full product of their common labor. I’ve already mentioned Marx’s critique of the “full product” half of that, and of course Marx also makes the point that “full product” is in tension with “equally” since different workers make different labor contributions. But what about his critique of the “equally” part of the equation?

Marx doesn’t criticize the Lassallean formulation on the ground that fairness shouldn’t be a concern, or that inequalities of any size whatsoever would be a-OK. Instead, he makes a series of points that anticipate exactly the sorts of considerations “luck-egalitarians” like Cohen would wrestle with a century and change later as they asked the crucial “equality of what?” question:

What exactly is it that we object to being distributed unequally?

We could have equality of compensation for effort, so that every hour of work at a given rate of intensity would be compensated with just as much consumption as every other hour of work at the same rate, but Marx points out that some people, through no fault of their own, might not have the capacity to work as hard or as long as others. We could just equalize consumption regardless of labor contributions but Marx points out that different workers have different consumption needs—“one worker is married, another is not; one has more children than another, and so on and so forth.” This is exactly the kind of thing that leads Cohen to settle on an egalitarianism of “equality of access to advantage.” It’s not unjust for someone on kidney dialysis to get more of society’s resources than someone whose only medical needs are an occasional Tylenol. It is unjust for your co-worker to make less than you because of differences in your unchosen physical or cognitive talents.

Marx cuts his exploration of these problems short, though, declaring that distributing rewards for labor in a way that’s objectionable in one or more of these ways will probably be a necessity in the first stage of a communist society in order to incentivize everyone to contribute as much as possible to building up the economy. But he holds out hope for the whole thing becoming a non-issue in a future state of general abundance under a really advanced form of communism.

There’s a line in this part that’s often quoted as proof that Marx rejects “transhistorical” standards of justice although it actually proves the exact opposite:

Marx says “right” can’t rise higher than the economic conditions at the basis of society. But how exactly are we deciding what’s higher or lower without a “transhistorical” standard of measurement?

Finally, he argues that the issue of how it’s fairest to distribute the “means of consumption” (what, in market societies, we call “income”) is ultimately secondary, because the grotesque level of inequality we see around is downstream of “the fact that the material conditions of production are in the hands of nonworkers in the form of property in capital and land, while the masses are only owners of the personal condition of production, of labor power.” We need to do something about that if we want to have any chance of bringing about a more reasonable distribution of the means of consumption.

And of course, in his analysis of capitalist exploitation in Capital—his actual analysis, not Heath’s strawman—Marx says the core of the problem is a combination of the laws of exchange governing any kind of market transaction with a historically specific distribution of property that creates a class of “doubly free” proletarians (legally free to sign a contract with any employer who will have them, and materially “free” from any alternative means of supporting themselves) desperate enough to submit themselves to domination and exploitation by selling their working hours to the capitalist class).

In other words, the structural exploitation built into the capitalist mode of production both rests on and reproduces considerable inequality. That’s one of several excellent reasons to want to consign it to the dustbin of history.

Whatever the merits of Heath’s explanation, I think he is right in his observation: between 1985 and 1995 there was a massive decline in the prestige of Marxism in analytical political philosophy, which paralleled what was happening in most other academic disciplines where it had a foothold. I think it is also fair to illustrate this with the difference in preoccupation between the Cohen of KMTH or Habermas of Legitimation Crisis and the Cohen/Habermas of the 1990s, with the hyper engagement with the correct normative principle of justice.

I don’t think it is particularly sensible to explain this development based on rational, immanent developments in the spheres of academic research. Broader social forces made class and socialism passé and gave rise to a “post-materialist” moralism on the left. This story is mostly told in terms of feminism or post-modernism but the obsession with analytical theories of justice fits as well.

I thought the problem he brought up assumed liberalism as a standard for Marxism. I get you see it differently with a "facts/value" distinction but assume for me a second that it's not. You can't measure marxian axiology, in a broader sense than ltv, by reverting to an individual standard. I'm not saying Marx denies individuals but it's clearly not the main focus of Marxism so much as labor relations. Obviously the two diverge somewhere even if only to the degree that Marxism takes it as a specific stage rather than their conception of a whole picture so even to a Marxist I can't see how that can be a standard for Marxism or even why it'd be convincing.

Also, a lot, if not all, even definition 1, of your definitions of liberalism can probably be made equivalent or at least different parts or facets of the same thing. Liberalism dogmatically assumes it is dealing with the base concept of a human as a choosing, willing thing. This is a very non-biological conception of a human and any biological conceptions of human rights are aresonantly attached to the 17/18th century conception of a human. That and politics is rather liberal democracy instead of other democracies.

The facts/value distinction I think is off though and even more so assumes a liberal conception of reality. It almost in itself implies some type of solipsism. In order to know a value, one must know facts about a thing. If you consider it a category error by conflating knowledge of a thing with a fact of a thing then you're stuck with the same issue for values as the "value" doesn't refer to the object but the person separate from the object. That distinction assumes a separate dimension of an individual is a part of the object necessarily rather than the object having a value in and of itself. If we think of values outside sociology, like in scientific terms, we have to deal with the value of the object in and of itself. This could be medicines for example. You're simply never in your life going to assert an individual value participates with a value of medication and to the degree a human does value medication, we all the sudden havethe same standard any medical scientist does. In that sense facts are equivalent with values. Similarly in strong enough ethical systems, like ones in religions, the facts very simply are the value. Religions are strong enough to include complete behavior models for facts where medicines won't so there's obviously a distinction but there's a bridge either way.