Thinking Harder About Justice: Rawls vs. Cohen vs. Marx (UNLOCKED)

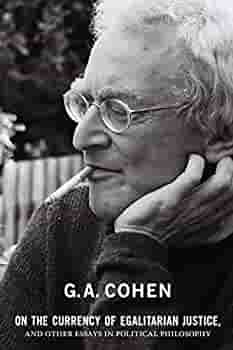

The Marxist philosopher G.A. Cohen is often understood as criticizing John Rawls's theory of justice "from the left." Let's take a closer look.

A little less than a year ago, I went on the Joe Rogan Experience. As someone who grew up watching sitcoms in the 90s, getting a chance to spend three hours drinking bourbon and talking politics with Joe from Newsradio was fairly surreal. Like I said here, I’m really glad I did it.

At the beginning of the conversation, I said that I was a socialist. He asked if I was a “democratic socialist” or a “straight-up socialist.” I answered that I do often add the word “democratic” because historically there have been lots of regimes that have called themselves socialist but haven’t had things I cared about like a free press and multi-party elections. And then I described my economic views in a “straight-up socialist” way.

What the question revealed is what I sometimes think of as the “Diet Pepsi” interpretation of the phrase “democratic socialism.” The idea is that the role of the adjective must be to indicate that the kind of socialism in question must be somehow milder or more moderate than “regular” socialism.

I think of it more like “regular coffee.” The same way “regular” clarifies that the coffee in question isn’t decaf, “democratic” clarifies that we’re not talking about an authoritarian distortion of the original ideals animating the socialist project. The point is to extend democracy from politics to economics.

In an effort to show that I mean “democratic” socialism the “regular coffee” way rather than the “Diet Pepsi” way, I followed up the point about political authoritarianism by both talking about the “socialist” reforms I’d support in the short term—Medicare for All, tuition-free higher education—and mentioning one of the reasons that I find capitalism as a whole so objectionable.

In other contexts where I’ve had a little more time to unpack the way I think these ideas fit together I’ve made the pretty standard socialist argument that inequality in economic power is the more fundamental problem underlying inequality in the distribution of income. (See, for example, here and here.) But one of the reasons that capitalist property relations are so objectionable is that they generate obscene levels of distributive inequality, and that’s the reason I stressed in the conversation with Joe Rogan. Here’s part of what I said in response to the “straight-up socialist” question:

Me: I do think that, like, the level of inequality that we get from the current system is indefensible—in other words, if one person has more than another just because they chose to work more, that’s one thing, right? Like, if Person A wants to stay at home and watch Netflix and Person B wants to work for more hours, then Person B can get more, I’m totally fine with that—but what bothers me is when you have these massive inequalities that have huge effects on people’s lives that are linked to things that aren’t under their control.

Joe: I would agree with you 100%.

The distinction I’m making here is one I lifted from the late Marxist analytic philosopher G.A. Cohen. This is the view he sometimes calls “luck egalitarianism” or the “socialist equality of opportunity” principle.

If you aren’t familiar with the details of that view, we’re about to get to it. First, though, for those of you who already know exactly what I’m talking about:

If (a) you know your Cohen, and (b) you’ve seen some of my debates with right-wingers over the last few years, you might notice an apparent inconsistency in what I’ve said about this stuff. I’ve referenced John Rawls’s Veil of Ignorance thought experiment a bunch of times in motivating my socialist views. Here I am, for example, bringing it up to Charlie Kirk at my debate with him a little over a year ago in Phoenix:

Charlie: I want to zero in on this because I think we have a really interesting point [of disagreement] philosophically. Do you think if someone takes a risk in America they should be able to keep the reward?

Me: Not entirely, no. I mean, you don’t think entirely…like, the only way you could think entirely was if you were an anarchist and you don’t think that. We should ask what are the limitations on that. I mean again I think the question you want to ask is if some transfer of wealth is justified because I think that’s the real question, right? When are transfers of wealth justified? And I think you need to go back to what are the principles that justify what you think a distribution of wealth in the first place should be. Now you could think that whatever kind of distribution you get letting the chips fall where they may in a free market, that that’s what’s justified…[but] I think the distribution of wealth that’s justified is the one that would emerge from the social contract that people would agree to under certain circumstances…if you were behind John Rawls Veil of Ignorance…

Charlie: Which I totally reject!

Me: I mean, of course you totally reject it! I mean, I’m happy to get into the theory of justice…yes you couldn’t believe the things you believe if you didn’t totally reject it but…I think if you want to know whether a tax system is just or generally whether a system of how property works is just you have to ask, if you knew you had to live in a society but you didn’t know who you’re going to be in this society would you agree to it and the same way if you didn’t know whether you were going to be black or white you wouldn’t agree to racial discrimination being part of the rules of your society, if you didn’t know whether you were going to be born into a poor family or a rich one, if you didn’t know if you’d have the particular skills to climb up the educational ladders of the professional-managerial class, if you didn’t know any of those things, how would you want the rules of society to work? And I think that’s going to be the answer that’s going to tell you when redistribution of wealth is justified.

So that’s me on record agreeing with Cohen in the conversation with Rogan and agreeing with Rawls in the conversation with Kirk.

But Rawls and Cohen disagreed!

Anyone with a detailed familiarity with debates about distributive justice in late twentieth century “analytic” political philosophy most likely has the following picture in their head:

Robert Nozick, out on the far right end of this spectrum, was a libertarian.

Cohen, on the far left, was a Marxist.

Rawls, somewhere in between, was a liberal.

Naturally, a Marxist like Cohen had a more demandingly egalitarian view about how resources should be distributed than a liberal like Rawls.

Right?

Keep reading.

Right-wingers often say that they’re all for “equality of opportunity” but they object to attempts to achieve “equality of outcome.” Jordan Peterson, for example, often stresses that distinction. Equality of opportunity is well and good but trying to achieve equality of outcome is a first-class ticket to gulags and mass starvation and the Dragon of Chaos ravaging the countryside. (I’m paraphrasing what he’s actually said, but honestly that kinda seems to be the gist.)

In Cohen’s very short and deceptively simple book Why Not Socialism?, which I wrote about here, he asks us to think a little bit harder about what “equality of opportunity” could even mean. Any conception of equality of opportunity is a conception of which barriers to some people achieving the better outcomes enjoyed by others are unjust.

What Cohen calls “bourgeois equality of opportunity” is all about “status restrictions” on achieving those better outcomes. “Status restrictions” in the sense Cohen means are restrictions based not on individual characteristics as they’re manifested over the course of someone’s life but on the category into which that person is born. Feudalism, for example, violates bourgeois equality of opportunity because there’s no procedure for someone born as a serf to advance to the “lord” position.

This often seems to be the kind of “equality of opportunity” that Peterson and other conservatives have in mind.

And this is an important kind of equality. Vast numbers of human beings have given their lives to achieve bourgeois equality of opportunity in contexts ranging from the Wars of the French Revolution in the 1790s to the Freedom Rides in the American South in the 1960s. This is the kind of equality that’s violated by slavery and serfdom and South African-style racial apartheid and Saudi Arabia-style gender apartheid and establishing bourgeois equality of opportunity, to the extent that it has been established in the world today, is a profound civilizational accomplishment.

But it only goes so far. This kind of equality of opportunity exists, for example, between the children of McDonalds CEO Chris Kempczinski and the children of people who work at McDonalds. Realistically, one generation’s outcomes become the next generation’s opportunities.

Stephen Jay Gould was surely right that for every Einstein there are God knows how many people with the same intellectual potential who we’ve never heard of because they spent their lives working in sweatshops. Conversely, put Hunter Biden in a working-class family and he’d be dead or in prison by now. And we can make the same point with much less dramatic examples.

Take a teenager who tests well and is good at processing written information but goes through a few rebellious years where she blows off school. Put her in a stable and supportive upper middle-class household and, long term, those years probably won’t hurt her much. She won’t be able to go to Princeton or anything, but if she decides sometime in her mid-twenties that she’s ready to give the whole college thing a chance she could be in law school by the time she’s thirty. Put the same teenager in a more chaotic and financially stressed environment and the probability of that outcome starts to shrink.

A truly exceptional runner might start a marathon three miles behind everyone else and still somehow win the race. The average runner who starts behind will end behind.

What Cohen calls “left-liberal equality of opportunity” goes further than “bourgeois equality of opportunity” precisely in trying to remove barriers to success arising from social circumstances. He gives the example of Head Start programs as an attempt to realize left-liberal equality of opportunity.

But what he calls “socialist equality of opportunity” goes even further.

Socialist equality of opportunity seeks to correct for all unchosen disadvantages, disadvantages, that is, for which the agent herself cannot be held responsible, whether they be disadvantages that reflect social misfortunes or disadvantages that reflect natural misfortunes. When socialist equality of opportunity prevails, differences of outcome reflect nothing but difference of taste and choice, not differences in natural and social capacities and powers.

That quote is from Why Not Socialism?. When he’s writing in a more academic register, in his classic paper Equality of What? On Welfare, Goods and Capabilities, the way he puts it is that the kind of equality that matters most is “equality of access to advantage,” where the word “advantage” basically means “anything worth wanting” and would presumably include the kind of economic power I talked about earlier. But for now let’s go with the “socialist equality of opportunity” language.

It's worth noting here that even achieving “left-liberal” equality of opportunity to any meaningful degree would probably already require smashing capitalist property relations—at the very least, you’d have to abolish inheritance!--but that’s a nitpick. The larger point is that the “socialist” equality of opportunity principle really does more fully capture the reason why the degree of distributive inequality generated by those property relations is so obscene.

To see the point, imagine a society ruled by a warrior caste. If you aren’t born into it, you can win a spot through trial by combat—and the only way to climb out of poverty is to do so.

One way of objecting to this is that it’s unfair that some people have to earn a spot and others are born with one. But that surely doesn’t exhaust our objections to this set-up. What if you happen to have been born small and weak? What if you have bad hand-eye coordination?

Of course, nearly anyone can get better with constant exercise and training, but the relevant cocktail of physical capacities just aren’t evenly distributed at the starting line. Even if we equipped this hypothetical society with a welfare state so everyone had a decent minimum, people with the physical ability to be warriors getting a vastly bigger share of the society’s resources than everyone else still seems like a stark injustice.

And exactly similar points apply to contemporary corporate capitalism. No one chooses not to test well, for example. Or to be too cripplingly shy to do the requisite amount of schmoozing to climb a career ladder. Again: Anyone can get better at these things, but similar amounts of work will pay very different dividends given different starting points. That’s true across the board. Most humans wouldn’t have careers in the NBA even if they’d done nothing all day every day from a very young age but practice basketball, and most humans wouldn’t be playing competitive chess on the highest levels if they’d never done anything but practice that.

It's fine to say that people who will be better at a particular job should do that job. It’s not unjust that someone who doesn’t have what it takes to be a lawyer or a surgeon isn’t a lawyer or a surgeon.

But that’s a completely separate question from whether people with other kinds of jobs deserve to have a substantially worse standard of living or substantially less power over their daily lives.

I know some of you people read A Theory of Justice before you were old enough to shave.

I mean, this is a philosophy Substack. There’s probably a disproportionate percentage of readers like that. I see you guys, I love you, and feel free to skip to the next section.

But I really hope I’m casting a wider readership net than just you people, so:

If you aren’t already familiar with these debates, you might not see yet where the divergence comes between Cohen and Rawls. Here’s a quick and dirty explanation.

If you were choosing societies from behind Rawls’s Veil of Ignorance, your first impulse would be to embrace something like the socialist equality of opportunity principle. But then it might occur to you that flatly disallowing any inequalities linked to factors outside of your control might be bad for you in some cases…even if you ended up being born with the short end of some of these sticks.

So, for example, if the society you were designing had to worry about constant barbarian invasions, giving some extra resources to the warriors to incentivize people to become warriors might work out better even for those who don’t have what it takes to be warriors themselves. And similar points might apply to incentives for people with unevenly distributed engineering skills in a technologically advanced modern economy.

Rawls’s “Difference Principle” thus states that justice doesn’t necessarily disallow distributive inequalities if the more privileged positions are (a) available to everyone under conditions of some fairly meaningful kind of equality of opportunity and (b) the inequalities tend to work out to the benefit of the worst-off people in the resulting society. I’m being deliberately vague about (a) because there’s a big open question about how substantial the equality of opportunity has to be to pass Rawls’s test, but if we interpreted (a) as Cohen’s socialist equality of opportunity principle, the issue we’re about to explore wouldn’t arise, so we’ll make the standard assumption that we’re talking about a less demanding conception than that. And (b) is simply the standard that the examples just considered points us toward. Inequalities pass that part of the test if the short end of the relevant stick is still longer than the equally-sized sticks of the more egalitarian alternative.

Some people think this is a free pass for the amount of inequality we have in contemporary capitalist societies, but that’s just philosophically, economically, and historically illiterate. You can need some distributive inequality to provide the kind of incentives that would pass Rawls’s test without needing anything approaching our psychotic level of inequality where the average CEO takes home hundreds of times the salary of the average worker.

Rawls himself was very far from being a radical firebrand in his political impulses. He accepted a National Humanities Medal from President Bill Clinton. From what I hear, he didn’t even like to sign petitions. He basically just wanted to sit in his study making abstract philosophical arguments and not making waves. But the logic of his position eventually brought him to quietly accept anti-capitalist conclusions in his academic work. In Justice As Fairness: A Restatement, published two years after he got the medal from Clinton—and just a year before Rawls’s death in 2002—he explicitly says that while Soviet-style state socialism is inconsistent with his theory of justice (because of its rights-violating authoritarian features), so is capitalism (because its severe inequalities disempower the majority of the population). He says that two options that are both consistent with his theory are “liberal socialism” and “property-owning democracy.”

He says so little about what “property-owning democracy” means that we can only speculate, but my sense is that the idea is that this would a society where the means of production aren’t collectively owned but where ownership has somehow been spread around in such small pieces to so many hands that there really isn’t a capitalist class distinct from the working class.

Even so, you might think, there’s a straightforward sense in which Cohen is “to the left” of Rawls. Since Cohen rejects the Difference Principle, Cohen’s Marxist socialism must allow less inequality than Rawls’s liberal socialism.

Here’s the confusing part, though:

There seems to be a fairly straightforward sense in which Marx is on Rawls’s side of the argument.

Before I unpack that last claim about Comrade Karl, a few caveats are in order.

First, there are numerous differences between the way that Rawls thinks about justice and morality and the way that Cohen thinks about these things that aren’t exhausted in “the Difference Principle, yay or nay?” One of the most important differences has to do with the proper scope of a theory of a distributive justice.

Rawls thinks that such a theory tells us how the basic political and economic institutions of a society should be structured, and that this is a largely separate question from interpersonal morality. Cohen disagrees. That’s a subject for another essay, but for now I’ll just note that (a) in Cohen’s Gifford Lectures, published as If You’re An Egalitarian, How Come You’re So Rich?, he acknowledges that his Communist relatives back in Montreal would have been on Rawls’s side of that argument as a matter of course—they would have thought all this moralizing about individual decision-making was largely beside the point—and (b) Rawls himself says that he’s following in the footsteps of Hegel and Marx in drawing the boundaries of justice in his institution-centered way. I am, for the record, firmly on the side of Hegel, Marx, Rawls, and the extended Cohen family on this one.

You shouldn’t have to wait too many Sundays for that to be covered on this Substack. For the moment, though, I’m going to restrict myself to the question of whether we should accept the Difference Principle and/or Cohen’s “socialist equality of opportunity” principle as a principle about institutional justice. Understood this way, Cohen’s principle tells us that, all else being equal, institutions are objectionably unjust to the extent that they tend to promote inequalities linked to factors outside of the control of the people who get the raw end of the deal.

“All else being equal” is important because there are obviously other values that have to be weighed against distributive justice. To simplify an example Cohen gives in in his book Self-Ownership, Freedom and Equality, if Person A has two working eyeballs and Person B has none, then—the ability to see certainly being an advantage!—the government can equalize A and B’s access to that advantage by forcibly confiscating one of A’s eyeballs to transplant to one of B’s eye sockets. That way they’ll both have depth perception problems but they’ll both be able to see.

I’ll shock you by saying that I’d be against that. So would Cohen. In this case, the competing claim from the value of individual autonomy outweighs the claim from the value of distributive justice. But more standard redistribution cases are importantly unlike that. As George Kateb put it in his classic review of Robert Nozick’s libertarian treatise Anarchy, State and Utopia, "I find it impossible to conceive of us as having nerve endings in every dollar of our estate.”

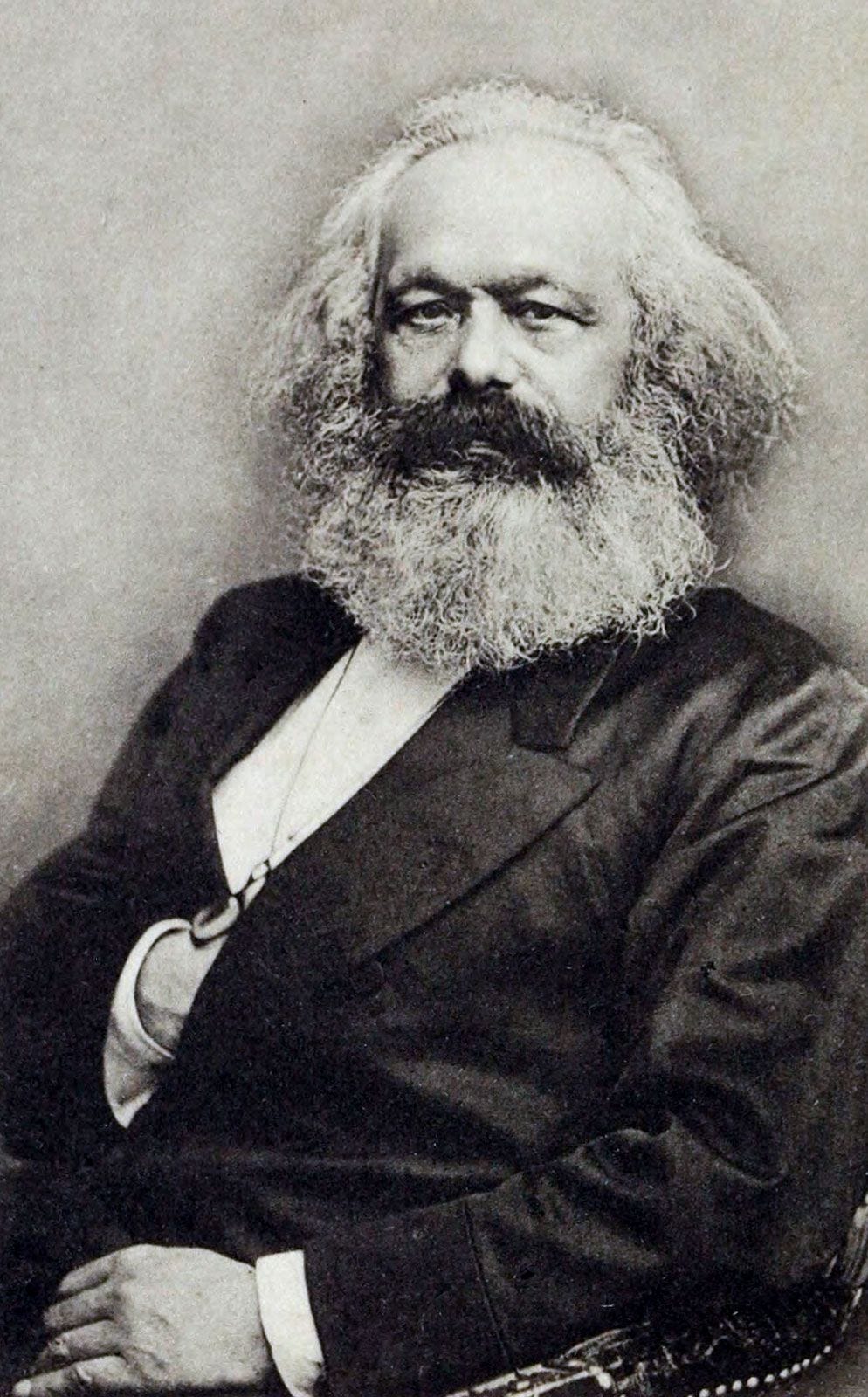

Finally, Marx was many things—the most insightful political economist of the nineteenth century, certainly, and an all-time brilliant analyst of historical change—but one thing he definitely wasn’t was a moral philosopher. Marx frequently expresses moral outrage about capitalism and other class societies, but he’s not in the business of philosophically reflecting on the underlying moral intuitions. His focus lies elsewhere.

When he does turn his attention to questions of distributive justice in his Critique of the Gotha Program, though, he makes a series of extremely perceptive distinctions.

In a famous stray remark in an introduction to one of the editions of Capital, Marx expresses disinterest in writing “recipes for the cookshops of the future.” While I agree with my friend Lillian Cicerchia, who argued in a recent article for Jacobin that contemporary Marxists should ignore his advice on this particular point—at this point in history, there’s just no way to overcome understandable cuation about radical social change without being able to say something concrete and appealing about what a new society might look like--I think I understand why Marx said it.

There’s an cliché about military strategy that says that no battle plan “survives contact with the enemy” and similarly Marx understood that if the working class seizes political power and starts to transform the economy, new problems will be encountered and new solutions would have to be devised that he couldn’t hope to anticipate from his chair at the Reading Room of the British Museum. As Rosa Luxemburg later emphasized, such problems have to be solved by the democratic deliberation of the masses—the solutions can’t be handed down ready-made by socialist intellectuals.

That said, Marx was moved to write a recipe or two of his own in response to some recipes offered by his factional enemies within the German socialist movement. The occasion was a unity conference at Gotha between different factions coming together to form what would become one of the most important left-wing parties in history, the German Social-Democratic Party. Marx wrote a critique of the proposed party platform, and in that critique he took special aim at the sloppy slogan that in a future society—what both Marx and some of his interlocutors called “communism”—workers should “equally” get the full product of their labor.

One of his objections is that if workers are getting back the full product of their labor, it won’t be equal, since different workers do unequal amounts of work. Another is that no society, regardless of the mode of production, can give the immediate producers back the “full” product of their labor, since some of it needs to be set aside for further production—fixing dilapidated machines, building new ones, and so on. And then, turning to what we’d now think of as questions of “distributive justice,” he points out that the citizens of any future socialist society would surely decide to set some of it aside for “common needs” like schools, hospitals, and the future communism equivalent of “poor relief” for those who are unable to work. Marx thinks such things—roughly the kind of services we’d associate with a “welfare state” today—would grow to take up a much larger share of society’s resources under communism.

Most interestingly, though, he also expresses discomfort with the idea of compensating workers, even after “deductions” for all the purposes just mentioned, with a level of consumption proportionate to what each worker put in during the process of production. Some workers have more consumption needs than others—for example, because they have more dependents. And compensating workers in accordance with the “duration or intensity” of their labor, Marx says, merely recognizes “unequal natural endowment, and thus productive capacity, as a natural privilege.”

In other words, not everyone can work as long, or hard, or effectively, as everyone else. Physical and cognitive capacities are unequally distributed. So far, Marx sounds a whole lot like Cohen.

But then he says that in the “these defects are inevitable in the first phase of communist society as it is when it has just emerged after prolonged birth pangs from capitalist society.” In other words, at this stage of communism it will be necessary to reward people unequally in proportion to their labor contributions in order to provide incentives for everyone to put in as much as possible.

Marx thinks that in the “higher phase” of communist society, once technological progress has created so much material abundance that there’s plenty to go around, and cultural progress has changed people’s attitudes towards labor, this inequality will be unnecessary—people can simply give what they can and take what they need—but until then, he seems to be saying, a bit of inequality will be temporarily justifiable for the sake of producing as much as possible to benefit everyone.

…which sounds a whole lot like the Difference Principle to me!

So does that mean that Marx is squarely on Rawls’s side of the argument?

Hold that thought while we look a little harder at Cohen’s side.

Remember that Cohen says that justice has to be balanced against other values. In the eyeball example, it was balanced against the value of individual autonomy. In Why Not Socialism?, he says one of the values it has to be balanced against is “efficiency.” If we don’t know yet know how to make the “wheels run” in a completely planned marketless economy, whether because of psychological problems about incentives or logistical problems about how to coordinate production with consumer preferences, some degree of justice may have to be sacrificed for the sake of efficiency, and we may have to temporarily accept some form of market socialism while we wait for the “red plenty” future of marketless planning.

He never quite says, at least in that book, where to draw the line—how much efficiency is worth some loss in justice—but a fairly natural thought is that the place to draw it is…exactly where Rawls does, at the point where more equality would actually be bad for the people holding the short end of the stick. He doesn’t say that, I suspect, because he doesn’t want to admit to himself that on some level he too accepts the Difference Principle.

And here he is in the introduction to his book Rescuing Justice and Equality, explaining the way the seed of the book grew in his mind from a conversation that he had with Tim Scanlon—a philosopher whose work would later be prominently featured in the NBC show The Good Place—in 1975:

“I said to Tim, with all due naïvete, that while I could see that it might be sensible for all concerned to offer unequalizing incentives to the more productive when the condition of the worst off would be improved as a result, I could not see why that would make the resulting inequality just, as opposed to sensible.”

At this point, it might be fair to start wondering whether the Rawls/Cohen dispute about the Difference Principle is—at least given all the caveats that I recited above—more of a semantic dispute about how to use the word “justice” than a substantive dispute about which distributive arrangements are the most desirable when everything’s said and done. Rawls, very roughly, thinks institutional arrangements are just as long as they aren’t objectionably unequal, all things considered. Cohen thinks they’re just if they aren’t objectionable unequal when we hold everything else constant.

This is in fact pretty much what I think but my last point here would be that, while we tend to call things “semantic disputes” when we want to minimize their importance, I think this one might be both semantic and significant. Both ways of using the term “justice” capture things that matter.

Rawls’s way of using it is important because it’s important to point out that what we’ve got now is monstrously unjust even in an “all things considered” way. And Cohen’s way of using it is important because it’s important to keep our moral attention focused on the fact that even if some arrangements are as egalitarian as we can reasonably get them for now, that doesn’t mean historical progress is over and we can just stop now. There’s a reason why Marx’s “higher” phase of communism is “higher.”

Some people say that, since Marx’s historical materialism tells us that what kind of new society can come into existence at any given point in history is a function of existing conditions, it doesn’t allow for any sort of “transhistorical” standard of justice, but that’s just wrong. In The Critique of the Gotha Program, Marx says, “Right can never be higher than the economic structure of society and its cultural development conditioned thereby.” That sentence is often quoted to justify the “no transhistorical moral standards” view, but as Cohen points out in his essay on Isaiah Berlin, it actually shows exactly the opposite. If the “right” of some societies is higher than that of others, there must be some sort of transhistorical scale on which we can make those comparisons.

Justice-in-Cohen’s-sense deserves to be part of our conceptual repertoire not because there isn’t a sense in which the Difference Principle is correct—there is—but because it’s a north star for future progress. Can perfect justice in this sense ever be achieved? Maybe not. Politics is complicated, we don’t make history under conditions of our own choosing, and there are always multiple values in the mix at any given time. But the reason to follow a north star isn’t because you expect your journey to take you to outer space. It’s because you need to know which way is north.

On the question of what “justice” means, I think Rawls makes an important point when he says that cancer isn’t just or unjust while a distribution of finite cancer medicines might be. In other words, for a state of affairs to be appropriately evaluated in terms of justice (as opposed to badness), it has to be the kind of thing that is the subject of social choice.

Rawls assumes that the basic structure of society is the subject of social choice. Hayek, for example, would deny that completely. Marx would agree, but he would say that social choice is constrained by the actually-available historical possibilities. One problem with Rawls from a Marxist perspective is that he is uninterested in suturing social choice in the immanent possibilities of the historical moment. So is a “property owning democracy” even a possible outcome of the present? If it isn’t, then saying it is what justice requires is like saying justice requires no one develop cancer.

What is peculiar about Cohen is that in his early career he is deeply interested in the question of historical possibilities but as he got older and neoliberalism appeared more dominant, he embraced a view of justice that is even more radically uninterested in historical possibility than Rawls