Analytical Marxism in the 1990s (UNLOCKED)

Wright, Levine & Sober's "Reconstructing Marxism" (1992) is a brilliant book. But we need to think harder than WLS do about how to steer away from left identitarianism and reconstruct class politics.

Three Sundays ago, I wrote about Erik Olin Wright, Andrew Levine & Elliott Sober’s criminally underrated book Reconstructing Marxism: Essays on Explanation and the Theory of History. That essay was called Historical Materialism in the 1990s and, as the title indicates, it was squarely focused on the “and the theory of history” part of Reconstructing Marxism.

This week, let’s do explanation.

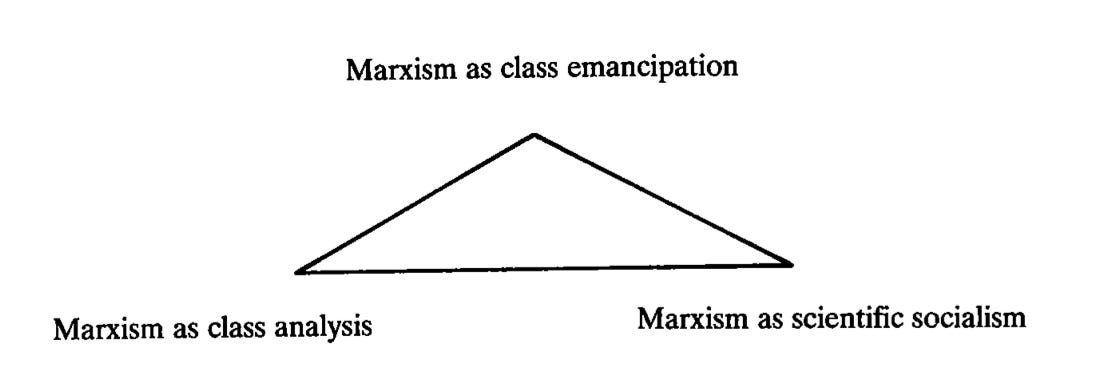

The last chapter of Reconstructing Marxism is called “Prospects for the Marxist Agenda.” In it, Wright, Levine & Sober (henceforth, “WLS”) give us a nifty illustration of a the “triad” made up of three things that “Marxism” can mean in different contexts—“Marxism as class analysis,” “Marxism as class emancipation,” and “Marxism as scientific socialism.”

“Marxism as class analysis” attempts to explain various aspects of capitalist society other than what goes on in the process of production by reference to Marxist class categories. “Marxism as scientific socialism” is the element of the Marxist project that “attempts to explain the developmental trajectory of capitalism as a particular kind of class-based economic system in order to understand the possibilities for socialism, and eventually communism.” Both are descriptive projects. However psychologically unlikely this may be in practice, it’s at least possible in principle for someone to coherently (i) agree that Marxist class analysis is a potent explanation for many aspects of the society in which he lives and that (ii) the “scientific socialist” claim that workers can and perhaps even probably will overcome capitalist property relations and institute a socialist republic while (iii) finding socialism abhorrent.

We can imagine the strange sort of literary character we’re describing blending a descriptive commitment to all these Marxist claim with a normative worldview derived from Nietzsche and Hayek. He thinks of the inevitable coming of the socialist darkness as an tragedy and he’s committed to keeping the light of capitalist property rights shining for as long as possible. Perhaps this character even acknowledges that the long-term possibilities are “socialism or barbarism” and he regards a descent into barbarism as the lesser evil.

The fact that what I’m describing is a “strange sort of literary character” and not any actually existing thinker who’s been a “Marxist” in either of these two descriptive senses, though, says something about the implicit importance of the normative dimension of Marxist thought. That’s “Marxism as class emancipation.”

WLS write:

The term "Marxism" has always led a double life: designating both a theoretical project for understanding the social world and a political project for changing it. Traditionally, these objectives were thought to be complementary: Marxist theory was to direct political practice, and Marxist politics was to direct the orientation and perhaps even the content of Marxist theory. In this sense, historically, Marxism has always had an "emancipatory" dimension. In its subject matter and its explanatory apparatus, it aimed to comprehend aspects of human oppression and, by theorizing the conditions for eliminating this oppression, or advance the struggle for human freedom.

Human freedom is a multifaceted thing. Feminism, for example, “constitutes a tradition of emancipatory theory built around gender oppression” while Marxism does the equivalent for class oppression.

The core normative ideal underlying the Marxist emancipatory project is classlessness, or radical egalitarianism with respect to the control over society's productive resources and the socially produced surplus. […T]he essential idea is that the existence of classes is a systematic impediment to human freedom, since it deprives most people of control over their destiny, both as individuals and as members of collectivities. In these terms, class relations in general, and capitalism in particular, violate values of democracy, in so far as the existence of classes blocks the ability of communities to allocate resources as they see fit, and they violate values of individual liberty and self-realization, in so far as class inequalities deprive many individuals of the resources necessary to pursue their own life plans.

While they grant that the “philosophical defense of this emancipatory project” has traditionally been a “relatively underdeveloped” side of Marxism, they think it’s always been part of the picture. (For the record, I agree.)

After introducing the triad, they write:

In classical Marxism, these three elements mutually reinforced each other. Marxism as class emancipation identified the disease in the existing world. Marxism as class analysis provided the diagnosis of its causes. Marxism as scientific solution identified the cure. Without class analysis and scientific socialism, the emancipatory critique would simply be a moral condemnation, while without the emancipatory objective, class analysis would simply be an academic speciality.

But remember that the title of the book is Reconstructing Marxism, not Defending All Aspects of Classical Marxism. They don’t think any of the “three poles of the Marxist tradition” should be abandoned. They see considerable vitality in all three. But they’re skeptical of the “unity” between the poles they attribute to classical Marxism. And they think even for each individual pole, the lines between the core Marxist claim and other theoretical traditions have become blurrier.

For example, on “Marxism as class emancipation,” they right that “until quite recently it was generally assumed that Marxist normative theory, if it existed at all, was at odds with liberal social philosophy and perhaps even, in crucial respects, incommensurable with it.” Now, they, say, “in light of recent work by analytical Marxists and liberal social philosophers,” this assumption has been “put under question.”

A recent illustration of this point would be the way figures like William Edmunson and Matt McManus have made use of liberal political philosopher John Rawls’s theory of justice in the last several years to argue for anti-capitalist conclusions. And whatever you think of this particular example, it’s hard to see why we should expect a clear bright line to separate Marxists’ normative ideal of class emancipation from a broader stream of “liberal” philosophical thinking about rights and equality.

On the descriptive front, one of the main points of Reconstructing Marxism is that what they regard as the intellectually healthy variants of the Marxist tradition had, by the 1990s, moved away from seeing Marxism (either as “class analysis” or as “scientific socialism”) as a radically distinctive “paradigm” in competition with “mainstream social science.” Instead, they want Marxists to make use of the social-scientific and analytic tools developed by mainstream academics to argue for Marxist conclusions.

So far, I wouldn’t really quibble with any of this. But what about WLS’s suggestion that, even if all three “poles” of Marxism are still defensible in their own ways, they don’t fit together within a rigorously “reconstructed” Marxism in the tightly unified way they did in “classical” Marxism?

This claim comes somewhat suddenly in that final chapter, and it’s not entirely clear (to me, at least!) what they mean by it. One obvious reading is that the fundamental conclusions of “Marxism” in each of these three senses don’t entail one another logically—but if so, it’s unclear to me that this is some sort of departure from Marxist orthodoxy. Did Marx believe each of these logically followed from one or both of the others? Did Engels? Kautsky? If so, I’d like to see some textual evidence.

One possible clue about what they’re getting at comes in a line I didn’t understand when I first read it. In the final paragraphs of the chapter, they say that "the jury is out” on “socialism's and communism's place in the broader struggle for human emancipation.”

At first, that seemed like a bizarre about-face after at least the possibility (and normative desirability) of socialism had been assumed throughout the rest of the book—whatever doubts WLS might have about its historical inevitability. Was the end-of-history atmosphere of the 1990s so corrosive that WLS decided at the end of the book they were willing to settle for social democratic amelioration?

But they key word here is “broader.” This line has to be read in conjunction with the claim a couple paragraphs later that “the prospects for a ‘unified field theory’ of emancipatory possibilities” has been “fractured”—and this passage a couple pages before:

Some Marxists have claimed that Marxism constitutes a fully general emancipatory theory, not simply a theory of the transformation of class oppression as such, but of all forms of socially constituted oppression. As we discussed in Chapter 7, such arguments usually take the form of insisting that class oppression is the "most fundamental" and that other forms of oppression—based on gender, race, nationality, religion, etc.—are themselves either directly explained by class, usually via a functionalist form of reasoning, or operate within limits narrowly circumscribed by class considerations. We do not think that there is any reason, in general, to support such comprehensive claims of class primacy…

Here, I get off the bus. And to see why, we have to turn to Chapter 7.

The first thing they do in that chapter is to bracket merely “pragmatic” questions. It’s easy to see how one factor can be more important than another relative to whatever any particular investigators happen to be interested in, but what they want to know is what it would mean for one factor to objectively be more fundamental than another. Next, they separate “quantitative asymmetries” from “qualitative asymmetries.” The latter are about different causes contributing to an outcome in different ways. The former are about one factor contributing more than another to an outcome in the same way.

Quantitative asymmetries can take a couple of forms. Plutonium is a more qualitatively significant cause of cancer than cigarette-smoking in the sense that a small amount of plutonium is more potently cancer-causing than equivalent amount of tobacco. Smoking, on he other hand, causes more instances of cancer. In either sense of “quantitatively more important,” there’s no particular problem with saying that class is a quantitatively more important explanation of various social facts than race or gender—but such claims always have to be assessed on a case-by-case basis. They see no general theoretical reason to think it’s going to be more important for everything or perhaps even for most things.

Historical Materialism in the 1990s

Every Tuesday night for the last few months, I went to a mezcal-heavy cocktail bar to meet with a couple other Los Angeles-based leftie academic types and very slowly go through Erik Olin Wright, Andrew Levine, and Elliott Sober’s 1992 book “Reconstructing Marxism: Essays on Explanation and the Theory of History.” We wanted to finish before the new year…

And while WLS acknowledge that there are ways in which class factors can indeed contribute to outcomes in qualitatively different ways than other factors, they’re skeptical that these asymmetries amount to the contribution of class being more fundamental. Even if class structures impose limits on the range of possible ways that society might develop (while, say, ideology or autonomous features of the state apparatus or social conventions about gender play a role in selecting outcomes within that range), WLS don’t regard limitation-of-range as a “more fundamental” contribution to outcomes than selection-within-the-range. If I prefer apples to peaches, and I’m presented with a bowl of fruit that includes apples but not peaches, both my preference and the composition of the bowl explain my having an apple, but they deny that one explanation is “more fundamental” than the other. While I’m less clear on this point, I think they might also just think it doesn’t make sense to ask “more” questions without a common yardstick which you just don’t have when two factors are causally contributing to an outcome in different ways.

Are they right about these abstract points?

Maybe, maybe not. Many of the distinctions they make are useful and reasonable, but as I was reading it the analytic philosopher in me thought some of their arguments were a bit too hasty. They never paused to consider some interesting and at least somewhat plausible ways in which one factor might be generally more important than another—for example, the idea that qualitatively different levels of explanation might be non-arbitrarily ordered such that some levels were “more fundamental” than others.

Whoever’s right about that, though, none of it is really relevant to my dissatisfaction with their dismissal—in a far more normative and political key—of traditional Marxist ideas about a “unified field theory of oppression.” Let’s just grant for the sake of argument that (a) there’s no qualitative sense in which one factor can be “more fundamental” than another and that (b) there’s no overarching reason to suppose class-based factors always (or even almost always) make a quantitatively more important contribution to any particular non-directly-economic fact about our society than other sorts of factors.

Fine. But remember when they bracketed those “pragmatic” questions that only arose relative to whatever questions happened to interest particular investigators? What if the questions that we’re particularly interested in are strategic ones about how best, as citizens of advanced liberal capitalist societies, to contribute to a world with as little oppression as possible?

There, I think there’s a straightforward case for the primacy of class. First, the most pressing injustices in most people's lives—even the lives of most members of identity categories who are marginalized in various ways—are squarely concerned with the distribution of material resources and the various social ills that come from getting the short end of the distributive stick. As Adolph Reed points out:

Asserting, for example, that a Black single mother downsized out of her steelworker job and facing eviction or foreclosure suffers from “triple oppression” doesn’t say anything about the sources of her circumstances—or how she might understand them, much less what she might do to improve them.

Moreover, addressing class-based injustices—either by building a stronger labor movement or achieving bigger and better social programs in the short term, or transcending capitalist property relations and building a different kind of society in the long term—is by far our most effective lever for reducing other forms of oppression. Women are far less likely to submit to inegalitarian or even physically abusive family relationships, for example, if they don’t have to worry about how they’ll be able to afford housing without contributions from a husband or a boyfriend.

Or take various racial disparities—in poverty and wealth, and thus in educational attainment, in housing, in incarceration, and many other areas. One strategy for addressing these disparities would be to push for racially targeted measures up to and including cash reparations. As figures like Reed are always pointing out, there’s a normative dispute lurking here. Do we really see the goal as a more demographically appropriate distribution of poverty?

But even if we put the normative dispute aside and just focus on the coarser-grained question of how to bring about the result that fewer black people live in poverty, go to substandard schools, live in high-crime neighborhoods subject to militarized policing and so on, what’s the best strategy?

Certainly not reparations, which is by its nature a proposal that tends to have relatively limited appeal to anyone outside the minority of the population who would be on the receiving end. It’s at least possible, by contrast, to see how majorities within every racial group could be convinced to fight for universalist economic measures. Achieving any kind of significant social change that goes against the interests of the powerful is an immensely difficult task under the best of circumstances. But it’s a flatly impossible task in the absence of majority support.

To be clear, none of this is to say either that no forms of injustice should be alleviated in the here and now in any way except for universalist economic strategies or that all non-directly-economic forms of oppression will simply wither away “after the revolution.” But there are solid and straightforward strategic reasons to make what Benjamin Fong calls “the socialist wager.”

The socialist wager is that the myriad issues facing contemporary society follow from a more fundamental1 material inequality and social unfreedom, and that a broad reorganization of society will dissipate concerns once thought to be intractable. Provide people security and freedom, and they will sort out their own problems. There is a certain faith in humanity, in that sense. Though there are undoubtedly reasons to support certain social causes along the road to that reorganization, much of what passes for “urgent” can fall by the wayside, or at least be reframed as downstream of the principled positions that socialists ought to hold.

That seems exactly right to me, and it brings me to the last point I want to make about WLS’s otherwise excellent book. There’s a point near the end where they talk about the feedback loop classical Marxists hoped for in which political practice would inform and enrich socialist theory—which they compare to “clinical” feedback to medical science.

They note that the decline or ideological reorientation of Marxist parties around the world had by the time they were finalizing the book in the early 1990s had, “for better or worse,” severed much of the feedback loop. And they try to look on the bright side, noting the far greater scope for theoretical innovation afforded by the decline of factors like the rigid orthodoxy the capital-C Communist movement once enforced on its intellectuals. That’s fair enough, to a point. But I worry that their overly hasty dismissal of class primacy shows the influence of a different kind of feedback loop—this one from the politics of left-ish academia, which by 1992 was soaking in identity politics and highly resistant to placing any kind of priority on class.

A lot’s changed since then—including the revival of socialist politics outside of academia even in countries like the United States where socialism had long been exiled to the outermost fringes of political discourse. Maybe, just maybe, we can revive a clinical feedback loop that’s not as rigid as the Communist one but that still makes socialist intellectuals less likely to think like intersectional “triple oppression” theorists and more likely think like Reed or Fong.

Presumably, this use of “more fundamental” can be read as “more fundamental relative to pragmatic considerations about bringing about a world with as little oppression as possible.”

Interesting how a book written in a completely different philosophical idiom could come to pretty much the same conclusions as Leclau and Mouffe’s Hegemony and Socialist Strategy. It is almost as though it is not the consciousness of philosophically-sophisticated intellectuals that determine their being, but, on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness.