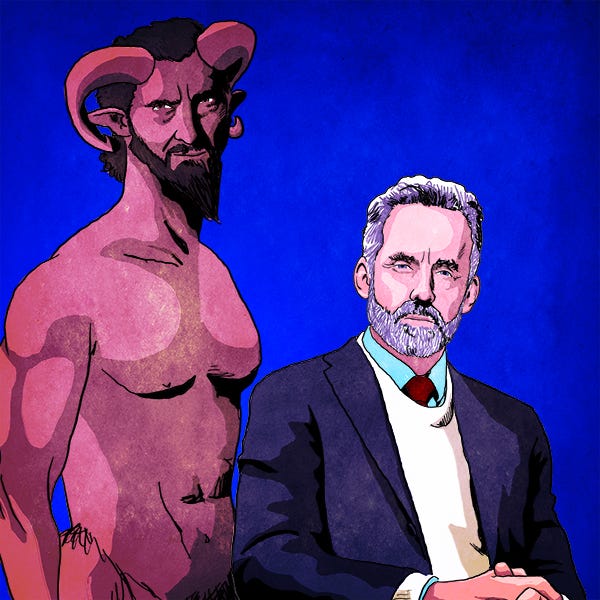

Jordan Peterson Thinks Atheists "Unconsciously" Worship Pan (UNLOCKED)

Peterson loves to score culture-war points by bashing atheists, but the closer you look at his own religious views--and his version of pragmatism about truth--the less clear it is what he believes.

I’ve spent way too much time thinking about Jordan Peterson.

In my defense, he’s an insanely popular commentator—far more so, I think, than some of my friends and comrades on the Left seem to realize.

Take his book 12 Rules for Life. It’s mostly unobjectionable and uninteresting self-help advice, although Dr. Peterson also sprinkles in an implicit defense of capitalism, some impressively inaccurate evolutionary theory, and a pages-long denunciation of something called “postmodern neo-Marxism.” The hardcover edition was released on January 23rd, 2018. A of the day I’m writing this, 12 Rules is still the #444 best-selling hardcover on all of Amazon. The paperback is the #162 bestselling paperback.

The paperback and Kindle editions sit at #1 and #2 in “Social Philosophy” and the hardcover is #3 in “Philosophy of Ethics & Morality.” (In that category, 12 Rules is losing—just barely—to the Meditations of Emperor Marcus Aurelius.) Again: This book was published more than five years ago.

Nor is the continuing public fascination with Dr. Peterson limited to his most successful book . Last year he joined Ben Shapiro and Jeremey Boreing’s depressing successful right-wing media company—the Daily Wire—and he was touted as a major acquisition. He was interviewed less than six months ago by the podcaster Lex Friedman, and that episode already has close to nine million views. When his professional association tried to make him go to a training he found insulting, it was a big enough deal for the head of the Conservative Party of Canada to weigh in on the controversy.

Like it or not, the man has an enormous audience. And since I’m in the persuasion business, I have to pay attention to him.

Or at least that’s my excuse.

The truth is that, while this definitely captures one of the reasons that I write about Peterson in political contexts, there’s something else going on here. It might be as simple as this:

I find the guy fascinatingly strange.

He wrote a wildly popular self-help book where the “B” is capitalized in every appearance of the word “Being” as an homage to Martin Heidegger. He thinks the twinned snake imagery common in ancient artwork is evidence that ancient people eating magic mushrooms had shamanic visions of the Double Helix structure of DNA. (He really said that. In front of a lecture hall full of adults. So confidently that no one laughed.) He’s weird. And clearly the kind of weird I find interesting—especially since, after all these years of paying attention to him, he keeps saying shit that surprises me.

For example, earlier this week I was absent-mindedly thumbing through my Twitter feed while I was sitting on a plane—and I discovered that I worship Pan.

If you aren’t up on your Greek mythology, I’ll save you the trip to Wikipedia. Pan is a god associated with nature and sex. He has a human head, arms, and torso, but the legs and horns of a goat. He plays a flute and he has a great beard and frankly there’s something very metal about him, so I guess I don’t find Dr. Peterson’s suggestion entirely unwelcome. At least my god is cool.

Granted, all of this is slightly unfair. Dr. Peterson didn’t actually say that I worship Pan. Hell, I might not even fall into the right category. I’m an atheist, but am I an atheistic hedonist?

I’m certainly not a “hedonist” in the philosophical sense. A “hedonist” in that sense believes that the only thing that’s intrinsically good is pleasure and the only thing that’s intrinsically bad is pain. Everything else that’s good—friendship, family, democracy, human rights, bodily autonomy, meaningful relationships, a sense of purpose, you name it—is good because it leads toward pleasure and away from pain.

I find Robert Nozick’s “experience machine” argument against that kind of hedonism pretty compelling. If you don’t know what I’m talking about, don’t worry, there’s sure to be a Philosophy for the People essay on the experience machine some Sunday in the future. But also don’t worry about it right now since I don’t think that’s the kind of hedonism Dr. Peterson has in mind.

A “hedonist” in the colloquial sense is just a particularly enthusiastic seeker after pleasure. If you’ve ever seen Futurama, think of Hedonism Bot.

And, hey, I enjoy whiskey and weed as much as the next guy, but I’m no Hedonism Bot—especially not at this point in my life. I’m a middle-aged writer and podcaster. I wake up early in the morning to walk my dog and file my articles. So maybe Dr. Peterson wouldn’t regard me as an unconscious Pan worshipper.

But the rest of his thread makes it pretty clear that I must worship some god or another.

All of this is a bit confusing. And the more we dig into what sort of god Peterson himself believes in or worships, the more confusing it gets.

Normally, I like Sam Harris about as much as I like Jordan Peterson. In fact, on the podcast I host (Give Them An Argument), we once did an entire episode called Sam Harris is Wrong About Everything. That was hyperbole, but I do regard Harris as being dead wrong about an impressively wide range of subjects—from airport security to free will and determinism, from IQ to “ticking time bomb” thought experiments, from meta-ethics to Palestine.

And I’ve never felt more sympathy for the guy than I did a few years ago when I listened to Jordan Peterson’s first appearance on his podcast.

This was from January 2017—a year before 12 Rules, when Peterson was first starting to rise to prominence for his crusade against Bill C-16. As far as I’ve ever been able to tell, that was an anodyne proposal to expand Canada’s pre-existing framework of anti-discrimination law to include gender identity so trans people wouldn’t be discriminated against in contexts like housing and employment. Dr. Peterson convinced himself that it was actually a law to force him to use trans people’s preferred pronouns.

At the time, the Canadian Bar Association chimed in to very politely suggest that Peterson was misreading the bill. He didn’t get any similar pushback on Harris’s podcast—but that’s not the part of the discussion that interests me right this second, because honestly they barely talked about C-16. They spent most of the episode off-topic, arguing about philosophy.

Peterson endorsed what sounded to me like a crude version of pragmatism about truth. Pragmatists reject the Correspondence Theory of Truth—according to which, roughly, a statement is “true” if objective external reality actually is the way the statement represents it as being. Instead, they analyze “truth” in terms of something like the goals of scientific inquiry, or some other criteria that’s about not external metaphysical reality but us—the goals and interests we’re pursuing when we make statements or accept the statements made by others as “true.”

I know I’m being a little vague here. But (a) different pragmatist thinkers have very different specific views, so I’m trying to cast a wide net, (b) I’m very far from being an expert on either the original pragmatists like C.S. Pierce or William James or more recent thinkers who’ve taken up some their ideas, and (c) it hardly matters because, while I’m not actually on board with even the most sophisticated versions of pragmatism—there’s a rock-bottom correspondence intuition I can’t get past—Peterson’s particular version of pragmatism is just immensely sillier than anything Pierce or James believed.

Peterson’s view is that things are “true” if believing them helps our species survive and thrive.

And, really, my heart went out to Sam Harris as I heard him try over and over again over the course of a two-hour podcast to get his new friend Jordan to see why that understanding of “truth” doesn’t make any sense whatsoever. What, he asked him, if a leak at a chemical weapon lab wiped out the entire human race—would that make the theory of chemistry the scientists were working with false? (Peterson’s response was…a lot of words, none of which showed much sign that he was registering Harris’s point.) All I could think was that Harris sounded like an overworked and underpaid adjunct professor trying and failing to explain a mind-numbingly simple distinction to the world’s most confused undergraduate.

When Peterson is asked point blank about his religious beliefs, he tends to say strange things.

A notorious recent example started with Peterson being told that to be a Christian you have to believe that things like the Incarnation and the Resurrection really happened—you can’t just “believe in them as symbols,” you have to “believe in them happening.”

Here’s Peterson’s response in all its glory:

So when I hear something like that, the question that arises for me is, what do you mean “happening”? So let me just unpack that a little bit. So I did a lecture at the Apollo last night on the story of Cain and Abel and one of the things that I proposed was that, not only did that story happen, but it’s always happening, it always happened, it’s happening right now, and it’s always going to happen into the future! So when I look at a story like Cain and Abel, the question, “Did that happen?” begs the question, “What do you mean by happened?” Because when you are dealing with fundamental realities and you pose a question, you have to understand that the reality of the concepts of your question, when you’re digging that deep, are just as questionable as what you’re questioning! So people say to me, what do you—do you believe in God? And I think, OK, there’s a couple of mysteries in that question. What do you mean “do”? What do you mean “you”? What do you mean “believe” and what do you mean “God”? And you as the questioner say, ‘oh, well, we already know what all those things mean except ‘belief’ and ‘God’ and I say no! If we’re going to get down to the fundamental brass tacks, we don’t really know what any of those things mean!

Now, this is not how Peterson talks when asked other kinds of questions about whether events happened. Peterson is very passionate about the horrors of Communism, for example. He even wrote an introduction to a new edition of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago. I’m pretty sure if you ask Jordan Peterson whether the famine in Ukraine in the 1930s “happened”, he won’t start droning on about how mysterious the word “happened” is and how we need to figure that part out before we can get down to the fundamental brass tacks. He won’t say that, in so far as the mythic archetype of an unjust ruler letting his people starve is so basic and fundamental, the Ukrainian famine has always been happening and will always happen. He’ll just say it happened. Hell, ask him if market efficiency exists, and I’ll bet he just says “yes.”

But is there an all-powerful being? Did that being create the universe?

I don’t know, man. What do, like, words mean?

Sometimes Peterson seems to take it for granted that there’s a God. In a conversation with Andy Ngo, he said that Antifa does violent things as “revenge against God for the crime of Being.” Not a lot of ambiguity there. It’s pretty standard evangelical rhetoric—there’s clearly a God, deep down everyone knows it, and the alleged non-believers really just hate His guts.

Other times he gets cute with it and says things like—and I’m quoting from memory here, but if this isn’t an exact quote it’s very close—“I don’t believe in God but He probably exists.” On at least one occasion, he said he was “amazed” at his own belief in the tenets of Christianity.

If you want to check if you share his amazement, here’s some context that last one:

In that. discussion, he said Jesus is unlike the dying-and-resurrecting gods of other mythological systems because there’s a record of a real historical Jesus. Although that record can be disputed. But it “hardly” matters what the historical Jesus was like because Jesus is the “union” of a historical person and a myth.

Got it?

Peterson often says that he “acts as if God exists.” I’ve even seen him call a “more precise” way of saying that he believes in God.

I’ve also seen him say that Sam Harris “acts as if God exists” because Harris isn’t tempted to act like Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment the way a real atheist would. But—wait—you’ll recall from the Twitter thread above that there are no real atheists. Everyone believes in and worships some god. Pan. Priapus. Whatever.

So, again: Confusing.

Maybe my favorite instance of Jordan Peterson Trying to Describe His Religious Beliefs comes in this conversation with Dave Rubin and Ben Shapiro.

Dave Rubin is possibly the dumbest man in all of political media. If he’s not, that’s the character he plays on TV. But, credit where credit is due, at the beginning of this clip he’s trying to ask a good question. Filter it through the Dave Rubin Translator, and it comes out something like this:

“Jordan and Ben, you’re saying a lot of God stuff, but what do you actually mean? Describe your actual literal beliefs and keep it simple.”

Jordan goes first, and of course he fails this assignment.

He starts off—and keep in mind that Rubin literally just told him to keep it simple—by talking about how wild and striking and amazing it is that Jesus says in the New Testament that there’s no way to the Father except through him. He never gets around to finishing that thought, though, because immediately distracts himself and pivots to slowly rambling his way through some reflections on evolutionary biology and psychology. We have twice as many female as male ancestors, he tells us, because all the ancient chicks wanted to get with a few super-chads. (I’m paraphrasing.) He talks about how lesser men would have evolutionary reasons to hierarchically subordinate themselves to the super-chads and arrives at the idea of a “spirit of masculinity” pervading our evolutionary history and says that the idea of God might just be a psychological echo of that…and then, with no argument or justification whatsoever, he randomly tacks on an assertion that “there’s a metaphysical layer underneath that” which the biology and the naturally evolved psychology reflect—”that’s the sort of the macrosm above of the microsm below.”

At this point, things are getting mystical and exciting. It sounds like he’s going to express a real-deal belief in an all-PKG (all-powerful, all-knowing, all-good) being who created and rules the universe.

But he just can’t.

All he can bring himself to assert about the “metaphysical layer” underlying the evolutionary story is that it has to do with “something about the structure of reality itself” and—this is an exact quote—this something about the structure “might involve whatever it is that God is.” And then he admits he isn’t sure about even that much.

Ben Shapiro basically responds the way a good classroom instructor does when an Intro to Philosophy student says something rambly and incoherent. You don’t grind the whole class discussion to a halt by saying, “I’m sorry but none of that made any sense whatsoever, I don’t know what you’re trying to say.” You say, “What I think Jordan is trying to say is…” and then you formulate an actually coherent thought that’s sort of in the neighborhood of what the student was talking about and you keep going.

So Shapiro starts talking about Thomas Aquinas’s proofs of the existence of God and he says that what Aquinas was saying is “basically” what Peterson just said.

But of course it’s not. Aquinas believed in an all-PKG being who created and ruled the universe. And even all that slightly psychedelic-y rambling about evolution and Jesus and the rest, all Peterson can bring himself to sign onto is a hopelessly vague metaphysical something-or-other that might or might not have something to do with “whatever it is that God is.”

This is Peterson opening his mind as far as it can open to real-deal theism. He’s giving it his all. And he can’t quite do it. Because when you get down to it Jordan Peterson is just as much of an atheist as I am.

What fascinates me about this is that Peterson’s views on truth add up to a permission slip for him to say, “Yes, it’s true that an all-powerful creator God exists,” full stop, with a clean conscience.

So why doesn’t he?

After all, he clearly believes that religious belief has great social benefits. Whenever Peterson quotes Nietzsche on the death of God, he always does it in a way that strongly suggests that Nietzsche was a concerned Christian warning us about a dire outcome for our civilization. Peterson could not be clearer on his belief that religious devotion is better than “atheistic hedonism” for the flourishing of the human race.

Put this together with his bargain-basement version of pragmatism, and he should have no problem saying that Christian doctrine is “true” without any of this “I don’t know what words mean” hemming and hawing. The fact that he doesn’t tells me that whatever his official philosophical beliefs, Peterson hasn’t fully broken from the Correspondence Theory of Truth in his heart.

He knows damn well that he doesn’t believe in God in the way he believes in the Ukrainian famine. And—give the man this much credit—he has enough of an intellectual conscience about it that, while he’ll fudge this stuff a little, he can’t quite bring himself to pretend outright.

The story of Cain and Abel “happened” and “has always happened” and “is still happening” in the sense that it’s a resonant story with valuable lessons. But surely the same could be sad of any number of examples taken from Tolstoy or Shakespeare instead of the Bible.

We all “believe in” and “worship” some god—whether Pan or Jehovah—in the sense that we all act in ways that remind Peterson of some god’s behavior or commands. But you might as well say we all belong to one Harry Potter House or another and the only question is which one.

Do you value courage and bravery? Gryffindor. Hard work and loyalty? Hufflepuff.

None of this means that Hogwarts literally exists.

In some ways, Peterson’s way of fudging the issue reminds me of nothing so much as a certain kind of Reform Rabbi or ultra-liberal Protestant minister whose definition. of “God” amounts to a frankly naturalistic pantheism—God just is the universe, and the universe pretty much works the way Richard Dawkins thinks it does—or some pile of words like “God is the force in all things that makes for justice and creativity and benevolence” which sort of ambiguously hovers in the vicinity of describing an actual specific metaphysical belief.

The difference between those guys and Dr. Peterson is that I feel bad about having spent even a paragraph making fun of them—because generally speaking, at least in my experience, these theologically ambiguous clergymen and clergywomen are lovely tolerant open-hearted people. If I can’t always puzzle out the sense in which what they’re saying counts as a form of belief in God, I also can’t summon up a lot of energy to get mad at them for being confusing. Let them do their thing.

But it’s a little much to see Jordan Peterson doing rage-filled anti-atheist culture war when he can barely get it together to pretend not to be an atheist himself.

Like...c’mon, man.

Just stop.

Be who you are.

There’s plenty of room for you in Pan’s congregation.

I enjoyed the fun at the expense of the bad doctor’s terrible skills of conceptual analysis. I think there is no doubt his statements on what it means to believe in God come ultimately from Tillich through Northrop Frye, and Tillich is also the source of the liberal Reform rabbi or Episcopalian priest’s response on these issues. (And Tillich goes back to Hegel and Spinoza). Frye was a dominant intellectual influence at U of T when Peterson got there and he always sounds to me like he is trying desperately to write an exam in Frey’s class in a way the great man would approve.

Frye certainly would say that the Bible, at its best, is to the history of Bronze Age Canaan and early principate Judea as Hamlet or Macbeth are to the history of medieval Denmark and Scotland. It would both be correct to say they are not good histories and miss the point, which is about psychological resonance.

For a reasonably friendly account of what the sophisticated present-day pragmatists believe about this stuff, I would recommend Huw Price’s “Naturalism Without Mirrors”