Fascism and Conceptual Analysis (UNLOCKED)

What are we actually arguing about when we argue about whether Trumpism is fascism? And can we find a less dumb way to have the argument?

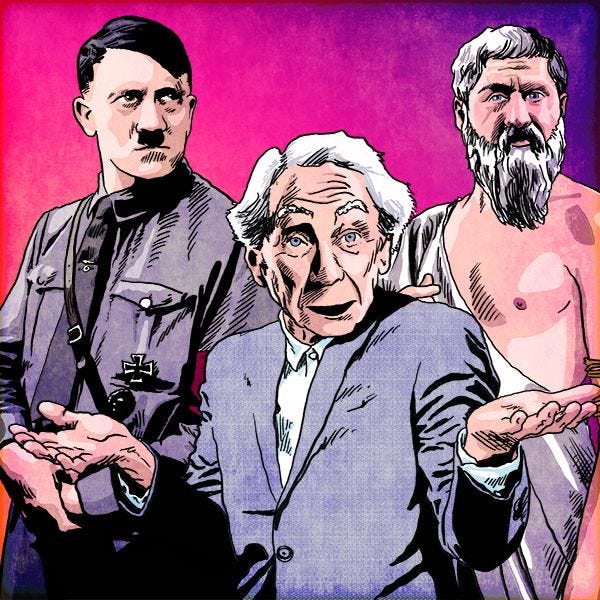

A week and a half ago, the New Republic published an editorial by Michael Tomasky with the title, “Yes, That’s Right: American Fascism” accompanied by a picture of Trump-as-Hitler. That seems unequivocal.

And the opening paragraph of the editorial bristles with indignation that anyone anywhere is unconvinced:

“No, no,” some admonish: “Don’t get carried away. Sure, Donald Trump is dangerous, perhaps uniquely so. But … fascist? The need to label him a fascist says more about the labeler than about Trump.” This argument has sprung from certain quarters of the right, which was to be expected, but it has also sprouted from the left, where a point of view has arisen that the “hysterical” invocation of the f-word is as much a danger as Trump.

That last bit, of course, is a strawman. I’ve followed the intra-left “fascism” debate reasonably closely for several years, and while lots of participants think the f-word is being misused, exactly none of them think such misuse “is as much a danger as Trump.” Putting that aside, though, the position the New Republic is sneering at seems clear enough—that of people “on the left” who "grant that Trump is dangerous, perhaps uniquely so” but regard fascism-talk as “hysterical.”

One might expect the remaining paragraphs to be spent laying out the case—explaining why Trump counts as a fascist (or under what definition of “fascism”). Instead, we get this:

We have trouble seeing the hysteria. We chose the cover image, based on a well-known 1932 Hitler campaign poster, for a precise reason: that anyone transported back to 1932 Germany could very, very easily have explained away Herr Hitler’s excesses and been persuaded that his critics were going overboard. After all, he spent 1932 campaigning, negotiating, doing interviews—being a mostly normal politician. But he and his people vowed all along that they would use the tools of democracy to destroy it, and it was only after he was given power that Germany saw his movement’s full face.

Today, we at The New Republic think we can spend this election year in one of two ways. We can spend it debating whether Trump meets the nine or 17 points that define fascism. Or we can spend it saying, “He’s damn close enough, and we’d better fight.”

But the interlocutors described above agree that Trump is “dangerous, perhaps uniquely so.” So presumably they would agree with Tomasky that he needs to be fought. The issue in dispute, clearly laid out in the first paragraph, is whether he’s a fascist.

Perhaps Tomasky and the magazine he edits are taking the position that Trump isn’t a fascist after all—making the headline poorly chosen and the first paragraph misleading—but rather that there are lots of important points of analogy between Trumpism and fascism. That, at least, is suggested by the turn of phrase about Trump being “close enough.”

But the only light the editorial shines on analogies between Trump and unambiguously fascist leaders is that one of those other leaders (Hitler) sometimes acted like a “normal politician.” Fair enough! But presumably most politicians who sometimes act like normal politicians aren’t actually fascists.

A more in-depth glossy-magazine intervention in this debate came at the end of March, when the New Yorker published Andrew Marantz’s long review of Did it Happen Here? Perspectives on Fascism in America, an anthology on the fascism debate edited by Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins. I suspect it was this book and the hubbub around it which inspired Tomasky’s grumbling about “whether Trump meets the nine of 17 points that define fascism.”

Marantz writes:

If Fascism is a distinctly historical phenomenon, something that took place only in Western Europe in the middle of the twentieth century, then it can’t happen here, by definition. (As the old Internet joke goes, it’s only true fascism if it comes from Italy; otherwise, it’s just sparkling authoritarianism.) As soon as you allow for a broader definition, though, the debate becomes more subjective.

And this is where, as someone trained in analytic philosophy, I start to get frustrated. It’s fine to say that “fascism” isn’t just the proper name of a historical development but a term for a phenomenon that could occur again. In fact, I think that it is! But how does that render the debate about whether recent examples count as instances of fascism subjective?

Quite a bit of philosophical energy, from Plato’s dialogues to Bertrand Russell’s essays to last month’s pile of academic journals, has been devoted to conceptual analysis—the attempt to provide necessary and sufficient conditions for the application of important concepts. You’re trying to figure out what “justice” or “knowledge” or “free will” is, so you carefully think about what features certain core examples of that thing have in common, use these to formulate a definition, and then your critics try to poke holes in the definition by coming up with actual or hypothetical counterexamples—cases that clearly are examples of the thing but which don’t meet your definition (thus showing it to be too narrow) or which clearly aren’t examples but do meet it (thus showing it to be too broad).

Like Tomasky, Marantz seems to have little interest in applying anything like this process here. Neither, more surprisingly, do even many philosophers who participate in the debate—Yale philosophy professor Jason Stanley, for example, is an energetic participant, but as far as I can tell his primary contention is just that there are echoes of fascist rhetoric in Trumpian rhetoric. Fair enough. But I would expect many right-wing movements, including lots that predated the rise of fascism, to draw on somewhat similar rhetoric. This strikes me as more of an example of the (uninterestingly obvious) fact that fascism is a phenomenon of the Right than strong evidence for the (far less obvious and more interesting) contention that there’s something distinctively fascist about Trump and the MAGA “movement.”

To be fair, Marantz, unlike Tomasky, does actually discuss at least one proposed definition:

[Historian Robert] Paxton, in his canonical 2004 book, “The Anatomy of Fascism,” attempts to define fascism in one overbrimming sentence: “a form of political behavior marked by obsessive preoccupation with community decline . . . in which a mass-based party of committed nationalist militants, working in uneasy but effective collaboration with traditional elites, abandons democratic liberties and pursues . . . internal cleansing and external expansion.” A nation in decline, which only one man can make great again? Trumpism clearly checks that box. Most of the others are more ambiguous. Death camps and Lebensraum—that’s internal cleansing and external expansion, of the prototypical fascist variety. But Manifest Destiny and forever wars? Is that fascism, or just America? When Trump told the Proud Boys to “stand back and stand by,” was he trying to collaborate with committed nationalist militants, or just mouthing off? Was Trump’s brutal approach to the southern border a step toward “internal cleansing,” or a more callous version of politics as usual?

Sadly, the New Yorker's house style, which requires that all subjects be approached with just the right amount of ironic distance, isn’t really conducive to a serious discussion on these points. This passage moves so quickly and breezily, for example, that it’s easy not to notice the slide from Paxton’s “a mass-based party of committed nationalist militants” to Marantz’s “collaboration with nationalist militants.”

It’s not a small difference! If anything’s distinctive to fascism as opposed to various other right-wing movements that are in one way or another ugly or authoritarian, it’s that fascism is a mass movement of street-fighting “militants” who, when they take power—annihilating opposition parties, organized labor, and other countervailing power sources in the process—supplement or even partially replace the traditional machinery of the state with their own forces. There’s not so much a world of difference as multiple galaxies of difference between that and purely rhetorical “collaboration with” a microscopically tiny group of nationalist militants with no power, no capacity to smite their enemies, and a multitude of federal indictments.

Full disclosure:

My friend Daniel Bessner and I co-wrote an article for Jacobin that was reprinted (as “What’s in a Word?”) in Did it Happen Here? The history of the Nazis’ rise to power lies within Prof. Bessner’s area of expertise, and our position was (and is) that, however bad Trump may be, the f-word doesn’t apply to him in any sort of literal sense. And if it’s meant in a looser and more metaphorical way, we still think the differences are more telling than the similarities.

We wrote:

Trump didn’t ride to power at the head of some street-fighting mass organization like Mussolini’s Blackshirts or Hitler’s Brownshirts. He stumbled into the Republican nomination for president because the GOP establishment was unable to consolidate against him in the way the Democratic establishment successfully consolidated against Bernie Sanders. Trump admittedly encouraged supporters to assault hecklers at rallies, though he backed off when he started to worry about his personal legal liability — a pattern of bluster and retreat that defined his presidency.

When the peculiarities of the Electoral College and the deep incompetence of the Democratic nominee allowed him to slip into office, Trump didn’t proceed to unleash an army of paramilitary supporters in an American Kristallnacht or take dramatic action to remake the American state in his image. In fact, as Corey Robin has repeatedly and helpfully emphasized, Trump was a weak president.

The Muslim Ban and his many attempts to escalate the war of ICE (an organization founded by Bush and used by Obama) on undocumented immigrants were disgusting and led to a great deal of avoidable human misery, but it’s also striking that, despite his best efforts to ramp up that machinery of repression, the overall number of deportations declined during Trump’s presidency. To the extent that Trump succeeded in governing at all, he mostly governed in the way that Mitt Romney or John McCain probably would have: cutting taxes, appointing union-busters to the National Labor Relations Board and social conservatives to the Supreme Court, and generally acting like a standard-issue Reaganite Republican.

We were writing this a bit over a week after the January 6th rioters tried to stop the certification of the 2020 election—an event that changed the minds of some popular historians who’d previously found fascism analogies unconvincing. Wasn’t this something like the Beer Hall Putsch?

Even there, Daniel and I considered the differences to be far more significant than the similarities. However quixotic it may have been, the Beer Hall Putsch was a real attempt by an armed and discipline paramilitary force to seize state power and institute a dictatorship. While it was effectively crushed at the time, significant elements of the German state were already basically sympathetic to Hitler’s politics—to the point that, after his arrest following the coup attempt, Hitler wasn’t even deported to his native Austria. (The trial judge said he couldn’t bring himself to apply the law to a man like Hitler, who may have technically been an Austrian citizen but “thinks and feels like a German.”) January 6th was, we wrote, a “spasm of impotent rage by a mob mostly made up of civilians and a president who egged them on and talked out of both sides of his mouth about whether he supported what they were doing, but who also made no real attempt to mobilize the power of the state to back them up.” In its aftermath, the legal system came down like a ton of bricks on the rioters and Trump himself declined to issue a single pardon. Ultimately, the whole thing underscored the extreme weakness of Trump’s position, and it’s instructive to compare it to the Brooks Brothers Riot which successfully stopped the Florida recount in the 2000 election and, in combination with an effective legal strategy, actually led to the successful overturning of the will of the voters.

In my experience, the debate about Trump and fascism very often goes like this:

Critics like Bessner or myself point out the numerous differences between Trumpism and clear instances of fascism. In response, we tend to hear a lot of things like, “Well, sure, that was classical European fascism. Twenty-first century American fascism isn’t going to be exactly the same as that. It’s going to have its own characteristics.”

And I can accept that much. Two things can both be examples of the same larger phenomenon while still being different from one another in all sorts of interesting ways. But where I get frustrated is that I never seem to hear people who say things like this actually spell out what it is that makes both of these forms of fascism as opposed to just members of the vastly larger set of things that are “right-wing and very bad.” And I get the uncomfortable sense that I’m playing a game in which I haven’t been told the rules.

“Well there you go,” I can hear some of you saying. “You think you’re playing an intellectual game. We’re fighting fascism!”

And this, I suspect, brings us to to the heart of the matter. I expect many readers will by this point in the essay be angry that I’m “minimizing” the badness of Trump or the dangers of Trumpism. But how am I doing that? Can nothing be bad or dangerous without being fascism? Do we really need to reclassify each new bad thing as a reincarnation of the interwar European bad thing to get ourselves excited about opposing it?

I understand that, in practice, intra-left discourse on Trump is often polarized between the positions that “Trump is literally a fascist” and “he isn’t even worse than Biden,” but there’s no reason those couldn’t both be wrong. As I noted in my article with Bessner, I held my own nose and voted for Joe Biden when I was living in Michigan in 2020—not because I thought Trump was a fascist but because I thought he was a Republican. I was worried about the consequences of Trump’s appointments to the courts and to the National Labor Relations Board. I still think those were real and important concerns.

That said, a lot has happened in the last four years, including a Biden-backed genocide in Gaza. Nick French wrote a good essay—When the Lesser Evil Means Voting for Genocide—that’s likely to be of interest to Philosophy for the People readers. It certainly captures a lot of what I’ve been feeling lately. Nick uses a classic point made by Bernard Williams about the limits of utilitarian moral reasoning to draw out the dilemma faced by swing-state voters. I’ll admit to being grateful that, as a California resident, the whole thing is a non-issue for me.

Of course, it’s a lot easier to find your way to the conclusion that voting for Biden in swing states should be an easy decision, genocide or no genocide, if you think Trump’s re-election would literally end American democracy.

So:

Would it?

I have my doubts. Trump was (mostly) a pretty ineffectual president last time around. Most of the most lasting damage he did would have been done by a President Romney—e.g. appointing the judges who overturned Roe v. Wade. Trump-hating “compassionate conservative” George W. Bush did far more to move the country in an authoritarian direction with the Patriot Act, indefinite detention, mass surveillance, and the rest—though, as bad as all this was, it left the fundamental structures of our system largely intact. (And again: He actually overturned the results of a democratic election.) Perhaps Trump would be more effective in his second term, having learned various lessons from the experience. You can’t rule it out. I also think democratic institutions can be weakened in various ways without being destroyed outright—whether by Trump or, say, a future President Rubio.

There’s a lot of wisdom in the simple observation that things can always get worse. (As Stefan Bertram-Lee put it to me last Sunday, if you can’t actually hear gunfire right now, that’s a pretty good sign that things can get worse.) But the miserable half-democratic structures we’ve got at the moment do a pretty good job of keeping things stable for our corporate overlords while the M-C-M’ death wheel Marx describes in Capital—money becoming commodities becoming more money—does its thing in the background. I suspect that, if we’re faced with a choice of “socialism or barbarism” as Karl Kautsky once claimed, at least in the short term the "barbarism” we’re facing looks less like the fascist destruction of ordinary bourgeois-democratic institutions than the dull everyday barbarism of diabetics in Ohio dying because they can’t afford their insulin and foreigners dying in airstrikes without Congressional authorization.

Given that (a) no one seems to be interested in sorting out the semantics of “fascism” through any kind of coherent process of conceptual analysis, and (b) the main practical effect of constantly repeating the f-word is robbing it of its emotional force, I’d gently suggest that a more useful way of going about this debate is to drop the framing device about fascism and just argue about the things that we’re actually arguing about, like:

How alarmed should we be at the prospect of Trump’s re-election?

To what extent is Trump continuous with previous Republicans like Bush and Cheney, and to what extent does he represent novel dangers?

Would Trump being elected this time make it more likely that Republicans would succeed in stealing future elections?

Should leftists in swing states pull the lever for Biden despite what’s happening in Gaza?

…etc.

These are all important questions. So why not just directly argue about these points, instead of routing it all through a strange and murky discussion of the semantics of “fascism”?

If nothing else, I suspect that doing things that way will result in a vastly less stupid conversation.

One more point. I think the name for this concept is simply bound to produce a confused debate for the simple reason that the concept of fascism has been elaborated for 80 years, but there were once mass movements who called themselves fascists. The move that is being attempted here is to label a movement that largely rejects the moniker with it anyway. It is much like the GOP attempt label Democrats as communists even though almost no Democrats call themselves that. The point is the historical smear for present political ends. That is why, in both cases, there is a strong hostility to historical analysis of these post-hoc charges.

Thank you Ben. I very much agree with this perspective, as someone with an MA focusing on the interwar years in Australia. I have even changed my level of alarm upwards regarding what happened on J6 (mainly because the hearings convinced me that Trump himself tried to do something there, rather than the real estate agent riot it first seemed), but do not think that impacts the fascism debate. We have a history of violent and lawfare attacks on democratic elections in our own history from Bush v Gore to the post-Reconstruction state coups, to a recent trend of the Texas GOP simply legislating away city powers that are ever used for progressive ends. These things are terrible and people should absolutely be alarmed about them.

But the fascism debate is about people who want to say Hitler in a political debate and still have the self conception of being the “adults in the room.” Some academics who love going on MSNBC are more than willing to play the “expert” in this charade (Tim Snyder jumps to mind). It is very silly. Thomas Zimmer recently did a two part essay where the first part concedes that he doesn’t think fascism is a crucial analogy but that Trumpism is indeed very bad. The second part attacks your camp for supposedly going easy on Trump. But the evidence for that is that you don’t agree with the fascism analogy. Your sin is simply depriving some MSNBC boomers of a talking point referencing WWII.