Are Souls Randomly Assigned to Bodies? (UNLOCKED)

Perhaps not, but it's unclear why Jeremy Kauffman thinks this excuses his inability to engage in the most basic forms of moral reasoning.

Jeremy Kauffman is, as I understand it, the leading thinker of the Libertarian Party of New Hampshire. I wrote about him here a while back.

Recently, he weighed in on the Haitians-in-Springfield drama. If you’ve been living under a rock for the past few weeks, the short version is that a lot of Haitian immigrants have moved to Springfield, OH. Many right-wingers seem to think some federal agency assigned them to live there. The reality is that immigrants have the same right to move around within the United States as native-born citizens, and clusters of immigrants from the same place often find themselves in the same place for boringly obvious reasons. (You move where friends or relatives have already moved, you move where you think someone you know might be able to help you get a job, and so on.) In the collective imagination of many conservatives, though, 20,000 Haitians were “dropped” in a small-ish city in Ohio. And some prominent voices on the Right, up to and including Donald Trump and J.D. Vance, have endorsed a genuinely insane urban legend about this population—that they’re kidnapping and eating people’s pets. The whole thing is about as close an analogy to the Passover blood libel as you’re likely to get in the United States in the 2020s.

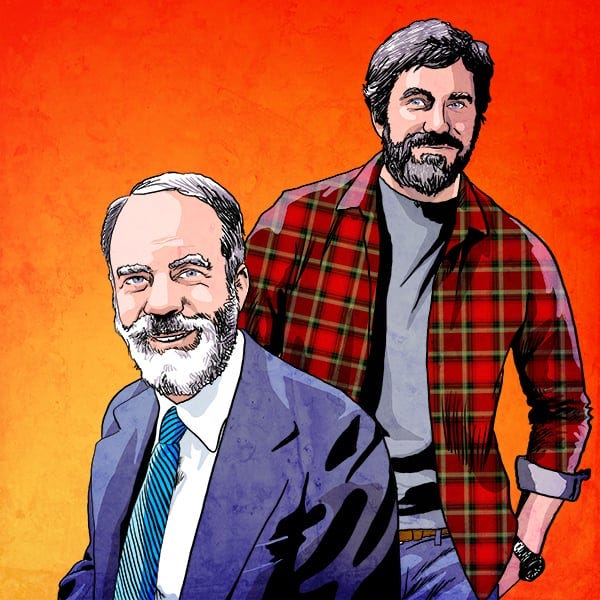

So, Haitians and anti-Haitian racism have been on a lot of people’s minds. Presumably, some goodhearted liberal somewhere encouraged people inclined to demonize this community to have a little empathy for what they’re going through. Naturally, Kauffman would have none of that:

The asininity of the second sentence is off the charts. Anyone interested in the actual origins of current conditions in Haiti should read this short article I wrote a couple years ago for Compact, or watch Ryan Grim’s exchange on the subject with Matt Walsh. But let’s put that aside for today and just focus on the first and last sentences. Why couldn’t he have been born a Haitian?

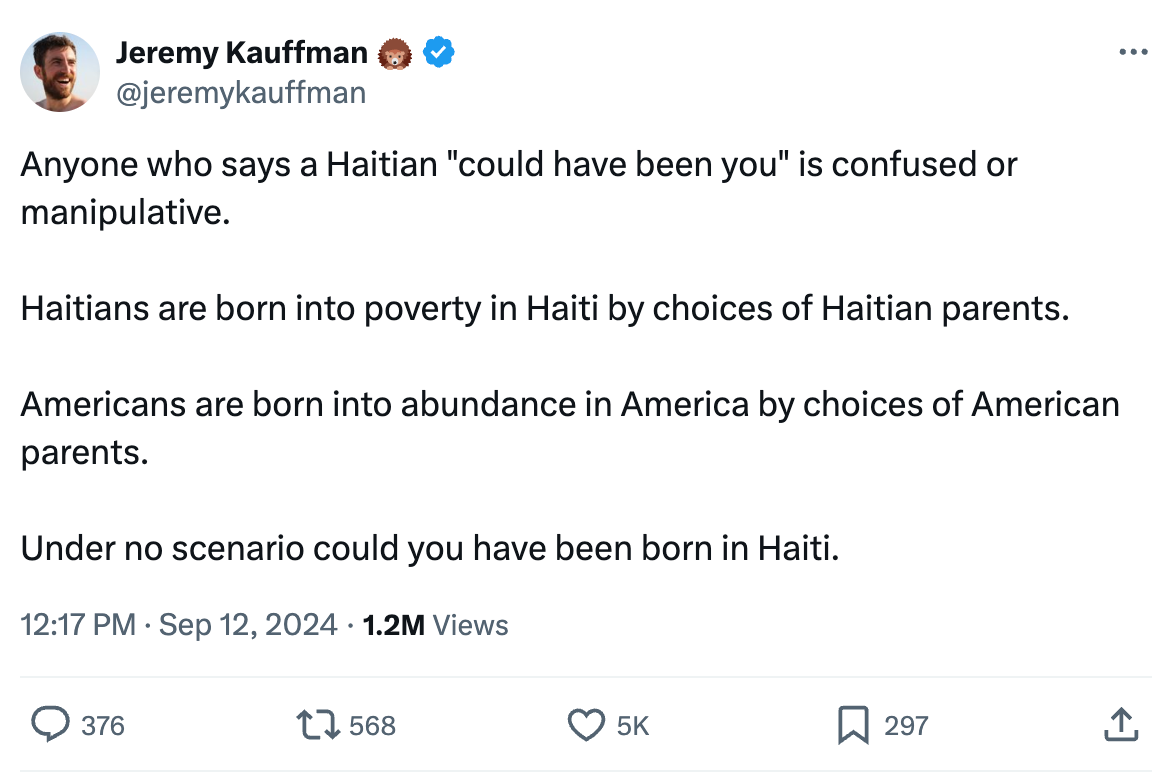

In a subsequent tweet, Kauffman rolled out some fascinating metaphysical reasoning:

Apparently, the only two options are souls being randomly assigned to bodies or there being no sense in which it’s correct to look at the experiences of a Haitian refugee and think, “That could have been me.”

This particular tweet leaves open the tantalizing possibility that, in Kauffmanite metaphysics, White American Souls are non-randomly assigned to White American Bodies and Haitian Souls to Haitian Bodies. To be fair, though, he actually seems to be some sort of physicalist about minds and personal identity. In subsequent discussion, he writes:

Fair enough. But, again, why couldn’t his material self have been Haitian?

The mug I’m sipping coffee from as I write this Substack was made by my late grandmother. It’s one of several pieces of her pottery I’m lucky enough to have in my kitchen. I don’t believe that mug has an immaterial soul, never mind one that was “randomly assigned” to it. I do, however, believe that it could have been different in any number of ways. Grandma could have made it a different color, for example, or a slightly different shape. Perhaps she could have even made it out of a different piece of clay. As we’ll see, some philosophers would resist that last claim, though it seems fairly plausible to me.

Kauffman says that there is “no scenario” where he, with his “brain,” his “personality,” and his “genetics,” could have been born in Haiti. Presumably, personality is a result of environment as well as genetics, so it’s true enough that if he were raised in a different environment, his personality wouldn’t be completely identical to the extremely charming one he has now. But surely he, with his genetics and, in some sense, his brain—let’s put aside environmental influences on brain development—could have been born in Haiti. It’s very easy to come up with a scenario where this happened. His mother could have boarded a flight to Port-au-Prince when she was pregnant with him, and, voila, he’s born in Haiti.

But perhaps this isn’t what he means. We could….charitably?…interpret Kauffman as meaning that he couldn’t have been born as a Haitian (rather than as a white American transplant in Haiti). But why not, exactly?

Perhaps the issue here is something like the “necessity of origins” thesis defended by the late philosopher of language Saul Kripke. Imagine that a (Haitian) child was born in Haiti on the same day in which Jeremy Kauffman was born in our timeline. This child’s parents die in a car accident on the way home from the hospital. Kauffman’s parents were unable to have a biological child of their own, and they adopt this child, name him Jeremy, and raise him in exactly the way they did. However unlikely this may be—remember that we’re trying to figure out what’s impossible here, so likelihood is irrelevant—let’s imagine that this child proceeds to have exactly the same life trajectory as “our” Jeremy Kauffman. He goes to the same schools, hangs out with the same friends, forms the same opinions, and so on, and as an adult he’s deeply involved in libertarian politics and he spends much of the day posting racist things on the internet. (Just for fun, we can build into our thought experiment that some sort of science-fiction machine was used on Baby Jeremy to change his skin color, and that he was never told he was adopted.) Would the resulting person be Jeremy Kauffman?

I think David Lewis would say “yes.” He thinks claims like “if X had been true, Y would be true” are true if and only if Y is true in “nearby possible worlds” where X is true. So, “if Julius Caesar hadn’t been assassinated, he would have eventually returned power to the Senate” is true if and only if Caesar did that in the closest possible worlds where he escaped the conspirators.

But what do we mean that Ceasar did that in those other worlds? Lewis doesn’t think any individual living in another possible world is strictly speaking identical to any individual in our world, so he thinks that really the counterfactual above is true so long as the “closest counterparts” to Caesar who weren’t assassinated in each of those other worlds returned power to each of their Senates. Presumably, the “Jeremy Kauffman” who had been adopted from Haiti, zapped with the Whiteness Ray, and ended up indistinguishable from our Jeremy Kauffman would be our Jeremy’s closest counterpart in that world.

Bodily Autonomy Has Nothing To Do With "Self-Ownership"

Jeremy Kauffman is a libertarian businessman and politician. Apparently he founded a “blockchain-based filesharing project” and he was the Libertarian Party’s nominee in the 2022 Senate race in New Hampshire. He’s also a big advocate of something called the Free State Project, which aims to encourage libertarians from around the country to move to New H…

Kripke, on the other hand, would definitely say “no.” Part of the disagreement has to do with a more basic difference about how he and Lewis understand what “possible worlds” even are. (I talk about that here.) But also, Kripke wanted to make sense of statements like this one:

“Aristotle could have died in his crib before he had a chance to make any contributions to philosophy.”

That seems true, and in fact obviously true. But we can make trouble for it on the “closest counterpart” view.

Let’s say the kid who otherwise would have been the closest counterpart to our Aristotle died in his crib, his parents tried again, and that their second son, who went by the same name (perhaps the baby died before being named!) had gone on to write the Nicomachean Ethics and found the Lyceum and teach Alexander the Great. Surely, that guy would be a closer counterpart to our Aristotle than the dead baby. But Kripke wants to insist that Aristotle wouldn’t have made any contributions to philosophy if he had died in his crib. He thinks the subject of the sentence is Aristotle, not “Aristotle or whatever counterpart of him you find lying around when you examine an alternate way the world as a whole could have been.”

Fair enough, but given that the “version” of Aristotle in any substantively different scenario would be different from ours in all sorts of ways, to make sense of the Kripke view you need some view of what “essential” properties our Aristotle and theirs need to have in common to both count as the same guy. And Kripke settles on origins. Sometimes he seems to suggest that their Aristotle needs to develop from the same zygote as ours, though his exact formulations tend to leave more wiggle room than this—a particular person wouldn’t be an alternate version of that person if they had come from a “totally different sperm and egg” and a particular wooden table wouldn’t be an alternate version of that wooden table if it had come from a “completely different block of wood.”

I have to say it’s at least not obvious to me that Kripke is right about any of this. My intuition is the same as his on Aristotle and Aristotle’s hypothetical Nicomachean Ethics-writing brother born after his tragic death in infancy, but I’m less sure about the table. Going back to my grandmother’s mug, if we consider on the one hand:

a possible mug with a different color and shape than the one I’m drinking out right now (but which she made out of the exact same clay)

…and on the other hand:

a possible mug that’s phyiscally indistinguishable from this one, that she would have made at the exact same time she actually made this one, but which she made out of a different piece of clay (perhaps because someone else at the pottery studio wanted the piece of clay she actually used)

…it feels fairly reasonable to me to describe the first scenario by saying, “she could have made a different mug out of the same clay” and to describe the second one by saying, “she could have made that mug out of different clay.” And even the human version of the necessity of origins starts to feel less clearly correct to me when I think about the parameters of what counts as a “totally” different sperm and egg. If Aristotle’s parents had gotten it on five minutes before or five minutes after they actually conceived him, it would have been a different sperm and egg. Perhaps not “totally” different in so far as the sperm-producer and egg-producer were the same, but this would also be true about the hypothetical Nicomachean Ethics-writing brother. We could try narrowing the parameters of “not totally different” but then conceptual trouble can still be wreaked by scenarios about twins.

And Kripke’s view here, no less than Lewis’s, is supposed to enable to us to resist the kind of counterfactual nihilism according to which nothing that isn’t true could have been true. (This is roughly what’s captured by “the breakfast question.”) But if the hypothetical alternate scenarios we’re willing to entertain are so constrained that conception has to happen exactly when it did, it seems like we’re inching close enough to complete counterfactual nihilism to defeat the point.

All of this is just to say that, while some version of the necessity of origins claim might be true, and certainly some of the motivations for it are fairly compelling, it’s at least far from obvious on balance that Kripke’s solution to the conceptual problems here is the best one. But just for fun, let’s assume for the sake of argument that it’s definitely and unambiguously right. Does it follow that moral arguments that proceed via role reversal thought experiments (“if you’d been born in Haiti…”), or reminders that it’s sheer dumb luck that Jeremy was born in less dire circumstances, are therefore nonsensical?

It absolutely does not, for two reasons. The first is philosophical and controversial, and the second is a blindingly obvious matter of moral common sense.

On the (Alleged) Plurality of Worlds

Last Sunday, I wrote about the multiverse and briefly touched on its purely philosophical equivalent—David Lewis’s theory of concretely existing possible worlds. Today, I want to say a little bit more about why I disagree with Lewis.

First, while many smart and thoughtful philosophers disagree, it actually does seem pretty clear to me that some but not all “counterpossible conditionals” are true. I learned the concept from this paper by Daniel Nolan, but here’s the rough idea:

In introductory-level classes, when we talk about logical impossibility, I’ll sometimes ask for a volunteer to draw something on the whiteboard for me. When someone comes up, I’ll hand them a board marker and tell them to draw a round square. Sometimes they’ll (understandably!) tell me they can’t do that, but often they’ll gamely try to draw something that looks kinda-sorta round-ish and kinda-sorta square-ish. I’ll ask the class if this is literally a round square, and they’ll agree that it’s not. I’ll ask if they judge the volunteer for not drawing what I asked them to, and they’ll say no again, because it would have been logically impossible for the volunteer to do what I had asked.

Well, this sentence seems pretty clearly true to me:

If the student had succeeded in drawing a round square on the white board, everyone would have been very impressed.

…while this one does not:

If the student had succeeded in drawing a round square on the white board, they would have died exactly three days later.

The first one seems to be true, in fact, because of the impossibility of the antecedent holding. But there seems to be no particular reason the second one would be true.

Well, if we can differentiate true from false counterpossible conditionals, then even if Kripke is right about the necessity of origins, various conditionals starting with the antecedent “if I’d been born a Haitian…” or “if Jeremy Kauffman had been born a Haitian…” could still be correct and informative.

Maybe you don’t buy that. Fair enough. As I said, I find Nolan’s point pretty compelling, but I can acknowledge that it’s a controversial claim.

But here’s the second and far more important point:

None of this even touches the core asininity of Kauffman’s tweet. Even if he wouldn’t be literally identical to the closest possible counterpart who was born in Haiti as a Haitian, and even if sentences like “if Jeremy had been born as a Haitian, then…” can when read literally refer only to alternate people who developed from the same zygote that produced our Jeremy, none of this touches the basic failure of moral reasoning on display here. And when I say “moral reasoning,” I don’t mean the kind you learn from grappling with Kant and Mill and Aristotle. I mean the kind we rightly expect from a reasonably emotionally competent 12-year-old.

Jeremy and I are very lucky that we were born in relatively safe and materially comfortable circumstances rather than in the poverty and chaos that have been inflicted on Haiti by centuries of nonstop imperial meddling. Assume the Kripke story about cross-world identity is true and this remains a correct statement. It can be cashed out as, “The difference between my or Jeremy’s lives and the life of a Haitian refugee isn’t due to anything Jeremy or I can control. We were born in better circumstances, but that has nothing to do with any choice we made.”

And if one child is cruel to another child and a parent or teacher is taking them to task by asking them to do a little role reversal (“imagine that it were you…”) they aren’t being asked to engage in complex modal reasoning that would require them to sort out whether Lewis or Kripke is closer to the truth about cross-world identity. They’re being asked to, well, imagine.

Think here about Kohlberg’s stages of moral development. I know various people have various thoughtful objections to this schema, but honestly I think it’s probably at least close enough to the truth for our purposes here.

A very small child might start being motivated to act well by nothing much beside the desire to avoid punishment. As they cognitively and emotionally develop, they get to the point where they can think a little more abstractly about rules and they follow those rules simply because those are the rules. If all goes well, though, eventually they get to the point where they can do some reasoning all on their own about what the right thing to do is in some situation, based not on what they think the received rules are but based on what they themselves think is fair or kind or reasonable.

Well, if anything even remotely close to the sort of picture Kolhberg paints is correct, I have no clue how you’re supposed to get to this “postconventional” stage of moral development if you can’t imaginatively project yourself into someone else’s circumstances. Note, not “form metaphysically correct hypotheses about yourself or your counterpart in a possible world where such circumstances held” but just imagine things being different so you were in someone else’s position, and use what you’re imagining to arrive at conclusions about how to treat others. Rudimentary moral reasoning doesn’t get much more rudimentary than that.

I don’t know how Jeremy got to this point in his life without acquiring that ability. But it might explain a lot about his politics.